Michael Parkes has worked as a planner since 1967 in public, private and community sectors in GB, the Middle East, Europe and Africa. Here he reflects on his work (1985 – 2010) in London as an independent Community Planner, both self employed; as Co-ordinator of Planning Aid for London, and then as a member of Community Land and Workspace Services (CLAWS) – the then GLC/LPAC’s Technical Aid Centre, and as a part time Lecturer at the Bartlett School (UCL). During this time he supported both small and large umbrella community groups including Spitalfields Community Development Group (CDG), the Kings Cross Railways Lands Group (KXRLG), The Finsbury Park Action Group (FPAG) and The Stonebridge Tenants Advancement Committee (STAC),

WHAT IS COMMUNITY PLANNING? WHY AND WHEN IS IT MOST NEEDED?

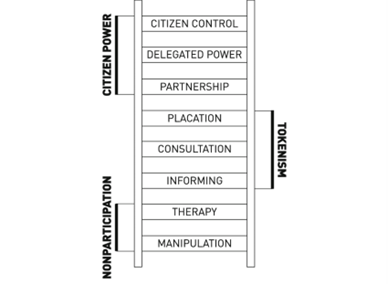

I worked throughout the Thatcher, Major and Blair eras and I think Sherry Arnstein’s Ladder of Citizen Participation says it all! (see Figure 1). Imagine the daily drama of heart and mind when working as an independent community planner on behalf of, and with, disadvantaged community groups. This involved challenging major public and private sector development schemes in which non- participation and tokenism in the planning and development processes were all too common. So I was supporting groups of people who were often not listened to, to bring forward better policies, plans and proposals, better ways and means of implementation and management.

Why? I sometimes used to say “after me comes riot”, meaning that if the wealthy and powerful ignore the grassroots, people who are angry, with little or nothing to lose, can and will, riot. After riot a Community Planning approach is essential. On the Stonebridge estate, for example, while riots did not actually happen it was described at the time by the Sun as “the most likely estate in Britain to erupt in violence”. In London, with cash strapped Public Authorities and high land and rental values, gentrification is a very real problem for some residents and small businesses. If you don’t own any land or buildings, then when land and rental values rise, you can be “squeezed out”. It may not be deliberate ethnic cleansing, but the impact is similar, serious, dramatic.

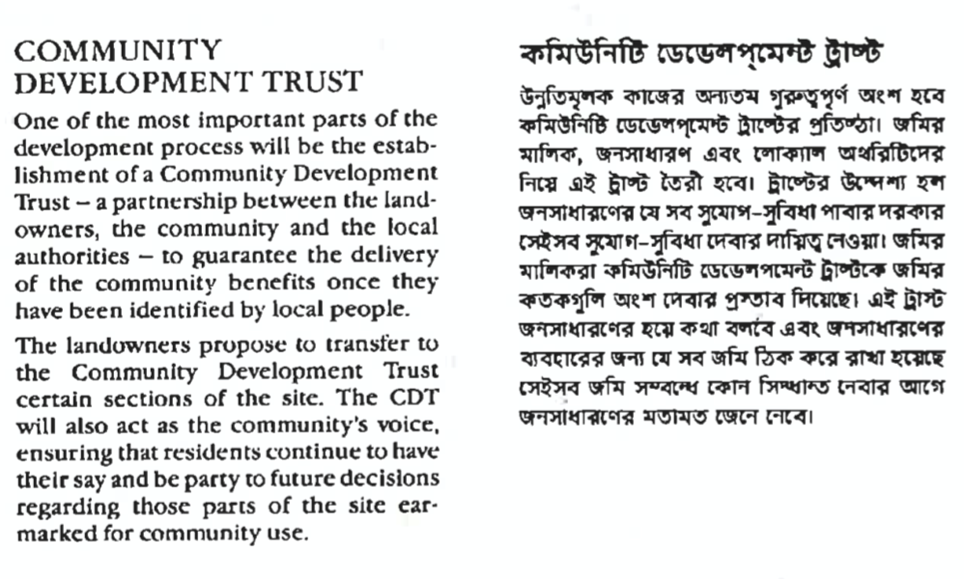

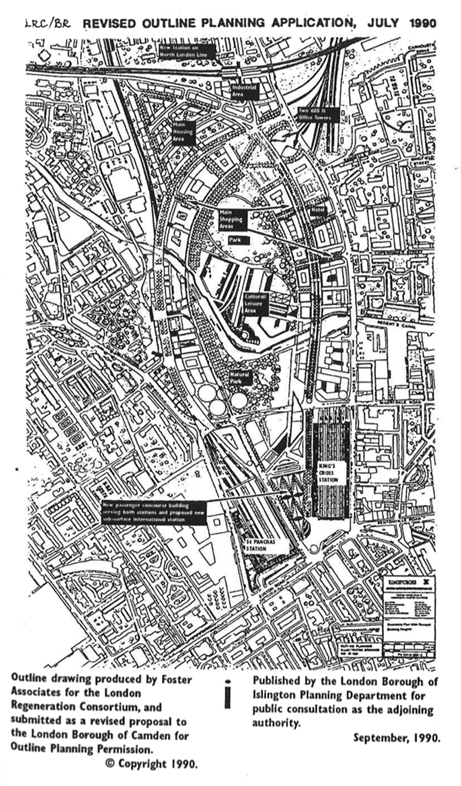

When? Hard-pressed disadvantaged groups are most likely to get involved when there is either a major threat or a major opportunity. An example of a major threat was the original Channel Tunnel rail proposal at Kings Cross, linked to 550,000 sqm of office development, including two 44-storey towers above ground on the 75-acre Railway Lands. An example of a major opportunity was Brick Lane in Spitalfields in the late 1980s when, in return for the exclusion of the proposed office part of the scheme from community involvement, the developer offered up front the transfer of valuable land into a Community Development Trust, most at no cost, the remainder at half market value. The office part of the scheme was on a relatively small part of the site, far from Brick Lane and already zoned for such purposes. The offer to transfer prime land into community control was a rare and major opportunity: a seriously bankable item; potentially a genuine partnership – a chance to get “a slice of the action”. Access to independent commercial valuation advice was made available to the Community Development Group (CDG) to ensure they got the best deal possible. Of course, the local Bengali community engaged immediately. (see Figure 2).

WHAT MAKES A GOOD COMMUNITY PLANNER?

Independence, relevant experience, optimism, empathy, respect and commitment are all essential for establishing trust and credibility. You work for the Community Group, not the Local Authority or the developer. If possible, see the whole process through (I was the KXRLG Planning Worker two days a week for 12 years). Where necessary, you will tell the group what they need to hear, rather than what they want to hear, and, of course, you need a belief in the power of people and People’s Plans!

SOME LESSONS LEARNED

The Community Group itself has to be demonstratively credible to maximise its political clout with the community, the Local Authority and, grudgingly, the developer. Credibility starts with authenticity, inclusivity and clear evidence of genuine community control. In all the work I did, people got involved who’d known nothing about planning or development. They learned as they went along. Some were squatters. Some were unemployed. Many had ‘ordinary’ jobs, but they were not ordinary people and their jobs were often essential. In my eyes they were heroes and heroines (true celebrities operating way below the luvvie/media radar). You know there is effective inclusion when the top priorities emerging are things like affordable housing, work, childcare, community safety and respect. Fissions and fractures within the group can undermine anything it puts forward. I’ve been in this position and it’s a difficult one to deal with (at Kings Cross we had two alternative Community Plans – one with a terminal and major office development at St Pancras, and one without).

The more community planning I did, the more I realised the importance of thorough preparation, such as the creation of a Management Committee with a Chair and Constitution and Working Groups with regular progress meetings, a time-plan, publicity, managing resources and getting the translations needed for a multicultural community. Good preparation is more than repaid in the quality of the product and effectiveness of the result. It helps credibility and follow through.

The more you can devolve different tasks to different Working Groups (housing, planning and the environment, transport, arts and culture, publicity, model making etc), the better you can engage a wide community, creating a strong umbrella group. Getting people volunteering with different skills, becomes a way of reaching out, creating ownership in the community plan and spreading the word. Respect and keeping everybody in the loop are crucial. In the process a community planner can access people and places no Local Authority or developer architect could ever hope to reach. This is essential for rich, well-evidenced and convincing Community Plans.

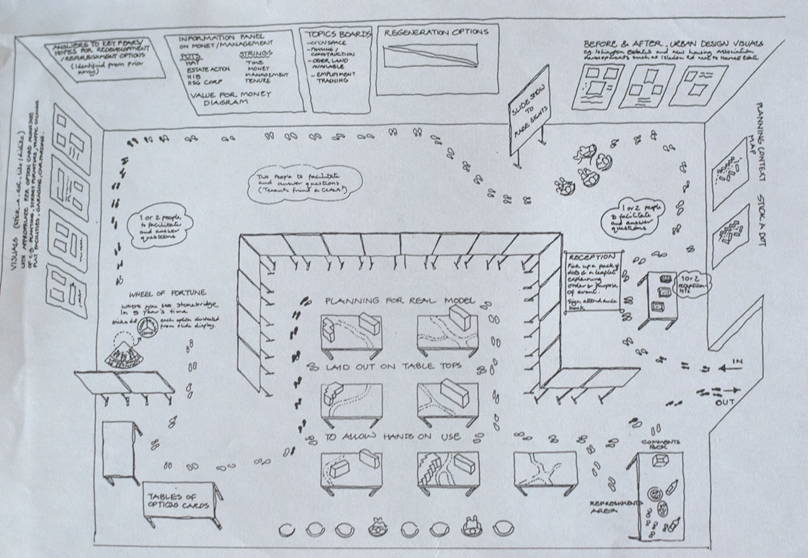

Also essential are a range of participatory techniques, such as model-making with Planning for Real (PFR), questionnaires or role play, such as acting out possible negotiations between the planner, developer and community. Directed by The Stonebridge Tenants Advancement Committee (STAC) and observed by Brent Planning Officers, probably the best PFR event I ever designed was with Community Land and Workspace Services (CLAWS). It was held in various locations on the Stonebridge Estate LB Brent in 1993/94. It had a theatrical quality, with different participatory elements laid out along a ‘route’, using screens so you didn’t know exactly what was coming next: ending up with the Wheel of Fortune, the PFR model, and tea, biscuits and samosas (see Figure 3). Stonebridge tenants learned from others who had already been through the same regeneration processes and could talk to independent professionals – architects, me, a valuer and an excellent ‘Tenants Friend’ -who provided independent advice on housing options and the various funding “pots and strings”. Total demolition was the preferred option. The Estate was eventually completely demolished and rebuilding has only just been completed, see here.

Partnership is high on the Ladder of Community Participation and I have tried to promote it wherever it was sensible to do so. A significant feature of the Spitalfields Community Plan (1990) was the concept of “Banglatown”, which emerged through the community planning work and envisaged a bazaar/ souk indoor market / small business development at the heart of Brick Lane. In helping to prepare this groundbreaking Plan, I was allowed by the Community Development Management Committee and my two Bangladeshi co–workers to, separately and at arms-length, regularly compare notes with Bethnal Green Neighbourhood Planning Officers and the architects (Hunt Thompson), who were employed by the developers (Grand Met/ LET). (see Figure 4).

Also crucial is that Community Plans recognise existing and emerging national, regional and local authority planning policies and proposals. You need to know about the approved development plan and policies so you can stand some chance of success. This happened with the Isledon Road Community Plan (predominantly housing and with a wide range of other uses) in the LB of Islington. This emerged from a series of Finsbury Park Action Group (FPAG)-organised local PFR events. It closely matched the Local Authority Planning Brief for the site. The developers’ alternative scheme for a major supermarket and car parking was withdrawn and the Community Plan was eventually built.

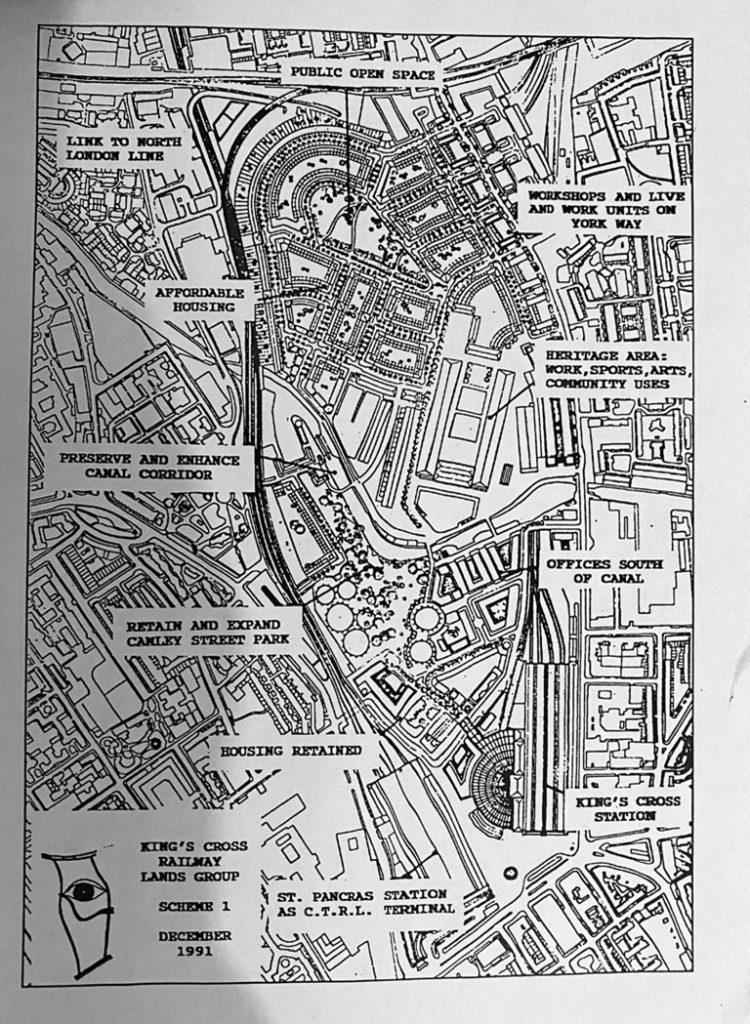

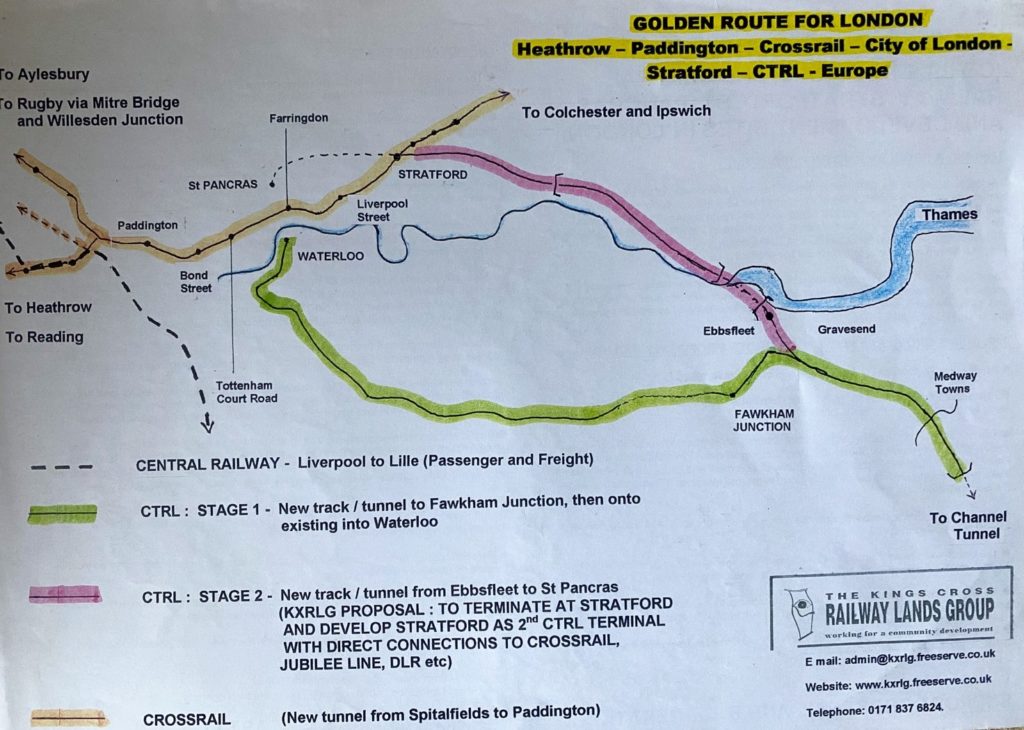

As for emerging plans and proposals, although never built, the work by KXRLG in 1990/ 91 at Kings Cross was important in helping change Government policy on the original route of the Channel Tunnel Rail Link (CTRL, High Speed 1) and above ground development of the railway lands site. In 1991 the KXRLG Transport Working Group backed the then alternative Ove Arup rail route from Folkestone via north Kent and London Docklands into Stratford and St Pancras. This was incorporated into the 1991 KXRLG Community Plan (Option 1) for the Railway lands. In 1994 the Government changed its mind and adopted the Ove Arup route. The combined change of policy on the routing of HS1 and the political clout and evident quality of the Community Plan helped not only to overturn the Norman Foster LRC Office City scheme, but also to influence the way the railway lands have been developed from 2007 to the present day – as a major office development confined to south of the canal.

If you want Community Plans to be built (as I do), keep your eyes on the property market and remember the need for schemes to be financially viable. This was a lesson we learned the hard way at both Kings Cross and Spitalfields. Neither Community Plans got built, in part because of a collapse in the London office market during the 1990s.

Remain optimistic! No community planner can expect 100% success. Even though neither Community Plan was built, a whole generation of local people were empowered. They gained skills, knowledge, confidence and social networks. I was walking down Brick Lane one day and I came face-to-face with a first-generation elderly Bangladeshi man who I’d met at a community planning event. I knew he had little command of the English language but then he started talking to me about a section 106 planning gain agreement and what they could get out of it. I thought, “Wow, if you’ve done nothing else you’ve spread the word about planning gain agreements!”

Phil, a fireman, chaired the KXRLG Management Committee. He became an expert on transport planning and Select Committee parliamentary procedures! (see Figures 5, 6 & 7).

Figure 6 (right): KXRLG Community Plan Option 1, 1991 (Good Practice Guide, page 134

WAY AHEAD?

In terms of contemporary development and regeneration, the days of people or profit are sadly a distant memory. The 1947 Town and Country Planning Act was a fundamental part of the Welfare State. The associated tax on the increase in development value conferred as a result of high value land use planning designation has long gone. Promotion of Community Development via land use planning designations and/or tax-based carrots or sticks seems unrealistic. For the foreseeable future, I suspect we are looking at planning and delivery based on people and profit. In high-value cities such as London, a Gold Belt of gentrification, including empty investment property, surrounds and extends out from the City Centre. Yet many essential, (as we saw during the Pandemic) remaining working-class communities and small businesses would prefer to stay and get a slice of the action. And I think it is strongly in London’s interest that they are enabled to do so. A pragmatic approach may be the best that can be achieved.

If the growing gap between the wealthy and powerful and the poor and powerless is to be bridged then, under the umbrella of the current Levelling–Up policy, whenever a major threat or opportunity occurs, Community Planning processes and resources should be available to working-class and ethnic minority communities as and when required. I am tempted to say that this should be mandatory. The process should be high quality and far better resourced than it is at present. Neighbourhood Planning in disadvantaged areas might present such an opportunity

In such situations, if Community Planning is to be embedded effectively in the conventional town planning and property development processes, then many of the lessons set out above need to be understood and applied. Effective partnership working and delivery vehicles, possibly along the lines of the Spitalfields model, need to be considered as and when appropriate.

In a future of people and profit, financial viability is crucial. Developers and community groups need to understand what motivates each other much better. Community activists and Town Planners, need to understand the process and economics of property development better. Both need access to independent commercial valuation advice. Developers and Town Planners need to understand the importance of “staying and getting a slice of the action” better.

Both at Spitalfields and Stonebridge, I was part of a team of committed and supportive professionals serving the local community. There may well be a case at regional planning level for the establishment of independent Technical Aid teams of architects, community planners, chartered surveyors, transport, legal and valuation advice similar to that provided to disadvantaged groups in London by CLAWS up until 1995. They will help keep the community plans realistic and credible, as well as helping Groups push for more out of a scheme.

Success needs the involvement and backing of professional influencers. Planning Aid, the Royal Town Planning Institute (RTPI), Town and Country Planning Association (TCPA) and (Rpyal Institution of Chartered Surveyors (RICS) as they all have an important contribution to make. So do universities who could and should provide independent technical aid themselves. They have an important part to play in training future town planners, developers and community activists gain a clear understanding of the People – Plan – Profit nexus.

Source: Good practice guide to community planning and development. Michael Parkes. LPAC. December 1995

Acknowledgements: Debbie Humphry, Sue Brownill.