Debbie Humphry (Oxford Brookes University) interviews Julian Agyeman, founder of the Black Environment Network (9th July 2022)

Debbie Humphry: Could you just tell me briefly about your involvement in community led planning, situated in a broader context of the idea of a Black environmental justice movement?

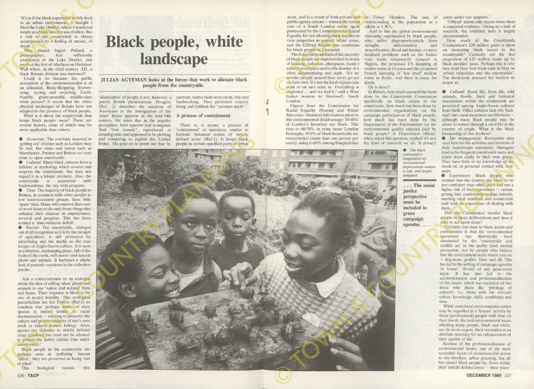

Julian Agyeman: I started out as a high school geography teacher. I taught in Carlisle for three, four years, starting back in 1982. This experience was really important in the later formation of the Black Environment Network (BEN) because being in Carlisle, of course, a lot of the field trips were to the Lake District. And there’s me, a Black teacher, leading a group of basically all white geography students and I used to notice how the hikers would sort of stare, and it was weird. I was wearing the right gear and clearly the teacher. So I started then to think about the English countryside as a White Space. And wrote quite a bit about it over the coming years. But really, it was quite a visceral notion. (Figure 1: Black People, white landscape by Julian Agyeman, TCPA Journal, 1989)

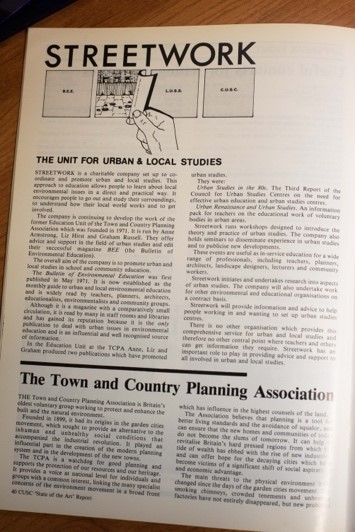

Then from 1982 onwards, I got very involved with a radical, anti-racist, anti-sexist geography journal called Contemporary Issues in Geography and Education. Now, again, geography is a very interesting subject. I mean, I was in a progressive Geography Department at St. Aidan’s school in Carlisle, but I remember going into the geography stockroom, and looking on the top shelf, and there were books like Homes Around the World – which was fascinating because it didn’t say we are going to take a developmental approach, but they started off with Aboriginal homes and finished the book with the semi-detached suburban house. So, you were being given a none-too-subliminal message of human progress from the ‘lowly’ people who were living in tents, to the pinnacle of human evolution: semi-detached suburbia. That’s what geography was. That’s the geography that my white English mother learned. That’s the imprints of colonial, empire-focused geography. So this got me going and, long story short, it got me really involved in radical, anti-racist, anti-sexist decolonial thinking about geography. Then I moved to London in the mid 80s and I was working for Streetwork, based at Notting Dale Urban Studies Centre, run by Chris Webb, who was a visionary. And I got introduced to the concept of Urban Studies (Fig. 2).

Debbie: One of our case studies is on the Golborne/Swinbrook plan in Notting Hill and we’ve found lots of archival material at the TCPA on the Urban Studies Centres, including the Notting Dale one.1

Julian: The name was taken from the book Streetwork: The Exploding School by Colin Ward and Anthony Fyson. Now, Colin Ward was the anarchist who did a biography of Kropotkin and Antony Fyson was the Education Officer at the Town and Country Planning Association.

Debbie: Yes, Colin Ward and Anthony Fyson were brought in to run the TCPA’s Environmental Education Unit in 1971, from which the Urban Studies Centres emerged.2

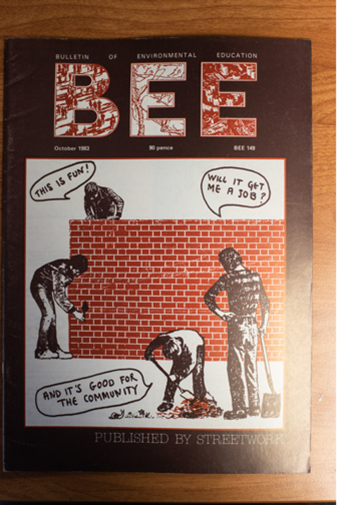

Julian: The TCPA was founded by Ebenezer Howard in 1899, so in a sense there is a lineage right back to these radical ideas of community planning of garden cities. So, yeah, at Streetwork we produced the Bulletin of Environmental Education – BEE, which was really exciting3 (Fig. 3). And this was my immersion and my shift. I was a biogeographer and ecologist, that’s what I loved, but when I got to London, in the urban environment, I became political. Because in the rural environment it’s very easy to kind of be apolitical and just do your ecological fieldwork. But doing urban studies, we were looking at bus services, where they go and don’t go. We were looking at housing accessibility and affordability and basically, what I didn’t know at the time, I was looking at British environmental justice issues. And this is where BEN comes in. I’d started to realise that in the US there was a movement for environmental justice. In 1982 Reverend Dr. Benjamin Chavis called out environmental racism, he created a new concept ‘environmental racism’. So, by the late 80s I was thinking, do we have environmental justice issues in Britain? And I suddenly realised that my experience in the Lake District was an environmental justice issue, where I, as a Black Briton, didn’t feel entirely comfortable going into some spaces. And that’s an environmental justice issue. Then some significant people came into my life and one of them was Ingrid Pollard, a photographer who produced this work called Pastoral Interlude. There’s a picture of an oilseed rape field in East Anglia with a guy in a suit, holding the Financial Times in one arm and a massive sugarcane in the other arm. And that’s me. And this is Ingrid inserting Blackness into White Spaces.

So, serendipity and a kind of roller coaster of events came to the point where in September 1988 we decided to set up the Black Environment Network. I was involved with Friends of the Earth, and we held a conference in London and got Jonathon Porritt to speak. Also, Reverend Barry Thorley, who was an author of the Faith in the City report, really damning of Thatcher’s Britain. And out of that conference came the Black Environment Network. The key figures were me, Ingrid Pollard, Vijay Krishnarayan and Roland De la Mothe, we all formed BEN. Then, as chair, I hired Judy Ling Wong to be the director. I was very motivated to bring the group together and formalise it and initially BEN was based in my home in Brixton. Where the hard work began. Because in the environmental justice movement in the States they’re talking about toxic dumping in low-income neighbourhoods, they’re talking about freeways, and we were thinking, is this really environmental Justice in the UK? Then in the early 1990s, both the Daily Telegraph and The Guardian did big spreads on rural racism, I did a piece on Countryfile and some colleagues made a couple of films that were shown on Anglia TV.

Meanwhile, in 1999 Friends of the Earth did a fantastic report that showed conclusively that the poorer you are in the UK, the more likely you are to have an unregulated power emitter in your area. But they didn’t introduce race into the report. And this has been, I think, a common problem in Britain, the tendency, certainly on the liberal left, to consider everything in terms of socio-economic status. Whereas in the US, the environmental justice movement was predicated on race more than socioeconomic class. Friends of the Earth called their report Pollution injustice, but in the US, the history of redlining and racist covenants meant that the whole urban planning project was predicated on racial segregation.

Debbie: Which is what you were wanting to do with BEN, and with Ingrid, creating representations that showed the racialised divisions in experiences of the environment. Do you think BEN had impacts?

Julian: Yes, undoubtedly. We ruffled feathers. I wrote quite a few pieces about the need for more black faces in white spaces, the need for more professional planners and environmental managers of colour. We heard at the time that Prince Charles had employed a Rastafarian Shepherd on one of his estates but found that none of the UK’s 25,000 countryside rangers were from minority groups. You said representation but I want to add the allied concept of recognition – as a precursor for justice. Because if we don’t recognise the existence of certain groups, how can we do justice by them? The brilliant late Iris Marion Young gave us the concept of recognition, which has given us a tool to understand how in the past discussions about environmental rights would pass people by, because they weren’t recognised. And the TCPA and groups like that who were white, they weren’t going to talk about certain issues.

Debbie: Interesting because the Notting Dale centre came out of a white, left, liberal intellectual position from the TCPA. Despite the area itself being a centre of racial conflict. How did the Centre seem to you at that time?

Julian: Well, to continue your point, this white liberal ideology was what I grew up in and race was not really a factor. At the TCPA, race was not a thing, these were Neo Marxists who really didn’t have a solid racial analysis. And the whole project of ‘New Times’, Marxism Today, the liberal left, turned a blind eye to issues of race. And in terms of urban planning in the UK, it really wasn’t there.

Debbie: Do you think there was even a language back in the 80s?

Julian: Well, there wasn’t a language at the time. Vijay Krishnarayan was one of the first people to look at issues of diversity in the planning profession, he did a paper in a Town and Country Planning journal. Because there was a lot going on in the Latimer Road area, there was the Maxilla nursery school, built under the Westway, which was revolutionary and multi-ethnic. There was a lot of thinking and action happening in the area. So, with the TCPA, I think I was one of the first disruptors, part of a group of people that got them thinking about issues of race. (Fig. 4)

Debbie: So, you were part of TCPA in its most radical days, when they were working on the ground, doing education projects, working directly with communities.

Julian: Yes, they were trying to do the right things, working with multiracial inner-city groups, but the TCPA was virtually all white. They were like white missionaries going into these neighbourhoods.

Debbie: How did the black people in the area respond?

Julian: Well, I think what the TCPA, what a lot of groups did, was adopt what I call a Colonial Leader kind of model. You know, they would find groups that were aligned with their ideas, and they would get into communities through those groups. So, it was a colonial model, developing allies. The TCPA needed these organisations so they’re trying to reach out. That horrible word ‘outreach’, you know, how can I get people to do what I want them to do? Where we decide what we’re going to do, and we get a few voices. And there was me, there was the emerging Black Environment Network. But this was Thatcher’s Britain, the late 80s. Green was abhorrent to Thatcher. So she was not going to be receptive to a bunch of Black people talking about green issues. And in those days Black people were very sceptical as well, ‘why do I want to go birdwatching?’. But we (BEN) were not talking about that. We were asking “What goes on in your neighbourhood?” The environmental movement narrative was wrong. If you were into environmental issues, you were a bird watcher or concerned about rare species. So, I would contest that and say, ‘look what’s going on around the world, in terms of climate change, we should have a voice in this. You know, why are our neighbourhoods not cleaned as much as other neighbourhoods?’ That’s where the injustice came. And services in poorer neighbourhoods were not as good, trash removal, street cleaning. You can change people’s behaviour through policy and planning but to change hearts and minds, to change values, you need to change the narrative to get people to think in a different way. Talk about Food Access makes you think about who gets access. Talk about Food Justice and the conversation focuses on our unjust food system. Changing the words means you just enter into a whole different way of thinking about possibilities. So, this is all part of my interest – challenging narratives, challenging orthodoxies, and thinking in different ways as a result.

Debbie: So, do you think from the 60s, 70s, 80s onwards, the black power movement, it wasn’t really about place – or was it?

Julian: I mean yes it was. If you look at Small Axe, the Steve McQueen series, there were clubs like the Mangrove in Notting Hill, there were several in Brixton, where I lived. It was never framed as community planning, but it was community planning. They used a different language, and this is why the TCPA and others didn’t get involved. Because the languages, the narratives, were part of the problem. There was the need in community planning for representation and recognition. But there wasn’t a common narrative around that.

Debbie: Did you feel that, when you were in London, did you feel the two worlds of community planning, with different people and different ways of doing it?

Julian: Yes, and in a sense, I was the bridge. And we wanted BEN to be the bridge. I mean, my mother’s white English, my father’s Black African, I was the bridge in the sense that I’m a product of a bi-racial marriage, so I can see these different worlds, and part of what I was trying to do was think about how they could come together. At the time, I didn’t have the wherewithal to know what was happening but now, reflecting on it, that’s exactly the space I was in. And it was quite a lonely space. There weren’t many people, other than the BEN people, talking about this, about justice and sustainability. In the planning departments around London, I worked with people who were all receptive, but they weren’t representative enough.

I stood down from BEN around 2004. It was Britain’s first environmental justice organisation, but I felt that it never really moved on from the rural racism work that we started with. It funded rural field trips for groups, Muslim women’s groups for instance, to go out into the countryside. And there was nothing wrong with that, but I felt we lost a critical edge. Environmental justice work should never be comfortable. If it’s comfortable something’s wrong. And so, I moved to the US where there was a critical narrative around environmental racism, and that’s what I’ve made my career about, revealing the increasingly intersecting goals of social justice and environmental sustainability, or what I call “just sustainabilities”.

References/Archives

Agyeman, J. 1988. ‘A pressing question for green organisations’. TCPA journal, London. February 1988.

Agyeman, J. 1989. ‘Black People, White Landscape. TCPA journal, London. December 1989: https://archive.tcpa.org.uk/archive/journals/1980-1989/1989/october-december-72/1613132

TCPA Journal No 12 December Page .17 – Town & Country Planning Association

Agyeman, J. 1994. ‘Making Local Agenda 21 Work’ TCPA journal, London. July/ August 1994 https://archive.tcpa.org.uk/archive/journals/1990-1999/1994/july-september-75/1614780

TCPA Journal No 7 8 July August Page 0006 – Town & Country Planning Association

Church of England. 1985. Faith in the City: a call for action by Church and nation / the Report of the Archbishop of Canterbury’s Commission on Urban Priority Areas, Church House Publishing, London, 1985

Fyson, A., 1976. The work of the TCPA education unit. Area, 8(2), pp.101-104

Krishnarayan, V. 1989 ‘Alternatives to the Status Quo’. Community Network: community planning and Technical Aid. Vol 6, no. 3, Autumn. A joint publication by the TCPA, on behalf of Association of Technical Aid Centres; Community Architecture Group, Community Technical Aid Centre, Planning Aid for London, Royal Society for Nature Conservation, think green; Town & Country Planning Association. London, p.7

‘Maxilla Nursery Centre’. 2020. Maxilla City

McQueen, S. Small Axe. 2020. TV Mini Series. https://www.imdb.com/title/tt3464896/ Broadcast on BBC https://www.bbc.co.uk/iplayer/episodes/p08vxt33/small-axe

Thomas, H. and Krishnarayan, V. 1992. ‘Planning Aid and black and ethnic minorities — a story of unrealised potential’. TCPA Journal. April 1992. https://archive.tcpa.org.uk/archive/journals/1990-1999/1992/april-june-75/1614100

Thomas, H. and Krishnarayan, V. 1994 Race and Planning

Ward, C. and Fyson, A., 1973. Streetwork: the exploding school. Routledge & Kegan Paul Books.

____

Julian Agyeman Ph.D. FRSA FRGS is a Professor of Urban and Environmental Policy and Planning and Fletcher Professor of Rhetoric and Debate at Tufts University, Greater Boston, USA. He is the originator of the concept of ‘just sustainabilities,’ which explores the intersecting goals of social justice and environmental sustainability, defined as ‘the need to ensure a better quality of life for all, now and into the future, in a just and equitable manner, whilst living within the limits of supporting ecosystems.’

Debbie Humphry is research associate on Spaces of Hope/PeoplesPlans.org

Footnotes

1 The Notting Dale Urban Studies Centre, Kensington & Chelsea was founded by the TCPA in 1974, embodying its ideals. It provided a collaborative and active learning environment for local, visiting and residential pupils, and operated as a community forum for local people and a resource centre for teachers, with an extensive urban archive. The TCPA provided a small grant to set up the charity, Streetwork Ltd, to continue the educational work after the TCPA Environmental Education Unit closed in 1982.

2. Ward and Fyson brought their practical teacher skills to the TCPA’s Environmental Education Unit, which was funded by Joseph Rowntree Memorial Trust and Elmgrant Trust. They promoted a do-it-yourself approach, along with a commitment to social and radical environmental action, grounded in Ward’s anarchism. The Unit’s distinctive approach was active Issue-based learning, in which children developed skills to research and suggest solutions to current issues in local areas. They also set up the Urban Studies Centres (CUSC) and were key figures in the TCPA shift towards involvement in local action in the 1970s and 80s.

3. The TCPA’s Environmental Education Unit produced a monthly Bulletin of Environmental Education (BEE) (1971- 83), which was a guide for teachers in the theory and practice of environmental education, with an emphasis on urban and ecological education. The journal was collaborative enterprise with articles authored by people from schools, colleges, Urban Studies Centres, careers centres and other voluntary sector organisations across the UK, sharing their experiences, resources and ideas around community-led planning.