John Le Corney, a south Londoner who’s kept his accent, moved to the Heeley area of Sheffield in 1975. As he recalled, in an interview for the Spaces of Hope project on 23rd November, he “more or less put a pin in the map”. Almost 50 years later, as John looks out over Heeley City Farm, he has a justifiable sense of satisfaction.

City Farms are now relatively common, but when the one in Heeley opened in 1981, it was one of the first. Back then, John was aware of them in a few places, like Nottingham and Leeds, but “I didn’t have any experience of them” and the one he helped establish didn’t come without a fight.

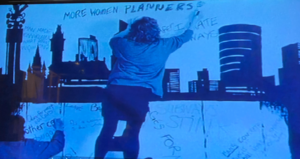

John arrived in Sheffield during an exciting period for community activism in the city. A rebellion was growing against an autocratic planning process reflecting an old-style of town hall politics and the post-war policy fixation with road building projects and “slum” clearance.

One of these projects was the Heeley Bypass, first proposed in the 1950s, approved in 1963 and due to start around the time John arrived in the area. He thinks one of the things he brought to Heeley was connecting the local situation with a national picture of opposition to road expansion schemes and top-down planning.

John also helped enlist a broad alliance of local people who wanted to fight the bypass, including trade unionists, Tenants Associations, environmentalists and sympathetic staff and students at the Polytechnic. They launched an energetic campaign of meetings, fly posting and protests.

Under this pressure, in 1978, the city council dropped the bypass. But the question of “what next for Heeley?” hung in the air. One consequence of the prolonged, but now abandoned road scheme, was the blighting of local housing, with owners reluctant to improve homes they thought faced demolition.

About 300 homes were affected, including some of the city’s last back-to-backs. Like in other parts of the country, the local authority was keen to replace them with new council housing. John remembers a meeting when tenants displaced by demolition were able to apply for these new homes, many of them choosing to stay in the Heeley area.

The demolition programme left about four acres of derelict land. The anti-road campaign had shown how powerful it was, but John says “we wouldn’t have this power for ever, so we went to the council and said “we’ve got this plot of land – we want to decide what happens to it”.

One night in the pub, the idea of a City Farm emerged, with the campaign using the “Three E’s” of education, environment and employment” as the headlines of its demands. With an initial three-year lease and help from various government training programmes, what is now a popular feature of the Sheffield landscape, with an annual turnover of a million pounds, was born.

John Le Corney attributes the success to the willingness of local people to share their energy and knowledge and the grassroots pressure that challenged the planning orthodoxy. As with other projects in Sheffield at the time, Heeley City Farm also connected with a shifting political outlook that tried, perhaps briefly, to connect local communities to the planning system.