Report by Debbie Humphry. Thanks to the participants who are quoted.

It took painstaking detective work to unearth women’s histories of community-led planning in Birmingham from the 1960s. After scouring archives, texts, exhibitions and films and sending out dozens of speculative emails, I was eventually rewarded with 12 online interviews with women who had been involved across the decades. This laid the foundations for an in-person Spaces of Hope workshop – ‘Women’s Histories of Community Planning/Place-making in Birmingham’ – in July 2022, which brought together 16 women who had campaigned for the spaces and places that women needed. They shared and mapped their struggles and discussed how these remarkable histories might provide useful lessons in the present day. It was exciting, invigorating and sometimes challenging to be with women who cared so much and had done so much to fight for a women, child and people-friendly Birmingham.

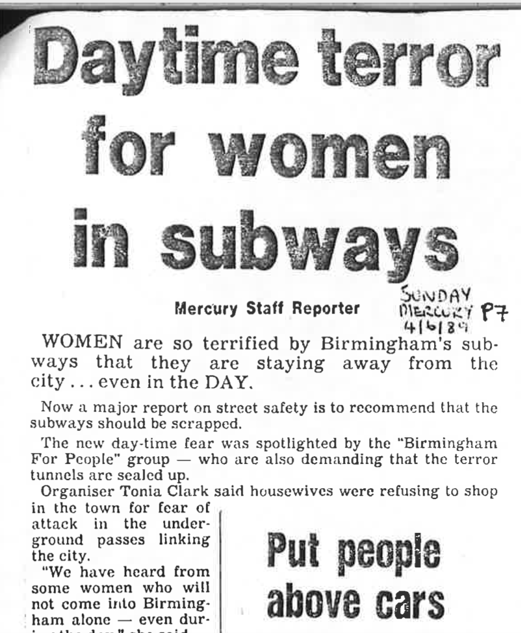

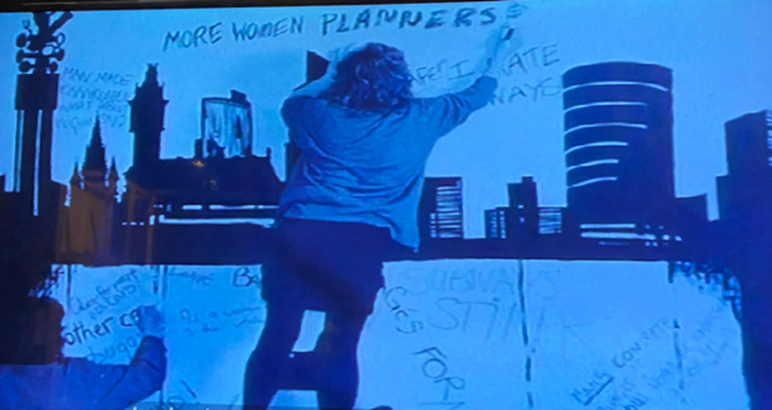

It was Heather Powell’s film Paradise Circus (1988), shown at the 2021 exhibition of the Matrix Feminist Design Cooperative (1981-1994) in London, that had first alerted me to women’s community planning in Birmingham. I was gripped not only by the film’s insightful exposure of the exclusion of women’s needs from mainstream planning, but also by the particular inequities imposed on women by Birmingham’s re-invention as a ‘business city’. Birmingham City Council had delivered perhaps the most widescale post-war modernist planning scheme in the UK, with extensive redevelopment from the 1950s, including areas cleared and redeveloped using system-built housing blocks, the development of an inner-city network of ring roads and, in the 1980s, the redevelopment of the central city as a business district. The city’s urban motorways that swept the visiting businessman into the central district and encircled it with a ‘concrete collar’ also cut the heart of the city off from its residential surrounds, pushing women with pushchairs and elderly pedestrians into dark, dangerous and disorienting subways: groups that bore the brunt of this discriminatory urban design.

Powell’s film showed how women had come together in different ways to research, represent and fight for feminist alternatives in a city perceived as reflecting social ideals privileging able-bodied professional car-driving men. Following up the leads, credits and themes from the film took me to a range of women who had fought for Birmingham’s authorities to include women’s needs in plans for the built and social environment. The women were variously informed by the women’s liberation movement, the Communist Party, the Green Ban movement, the New Left and third wave feminism. In the 1960s and 1970s women had created self-run creches, play spaces and adventure playgrounds, as well as safe houses for victims of domestic violence and women needing confidential health and pregnancy advice. One woman used a small inheritance to buy a terraced house in Balsall Heath for the sole purpose of setting up a safe house for sex workers. Similarly, about a decade later, in 1986, two pioneering nuns opened up their terraced home in Balsall Heath as a drop-in centre for local women involved in prostitution and vulnerable to exploitation, established as Anawim and still running today. The 1980s was also when the first ‘Gentleman and Father and Baby room’ was opened in Birmingham’s’ Ashram Community neighbourhood centre.

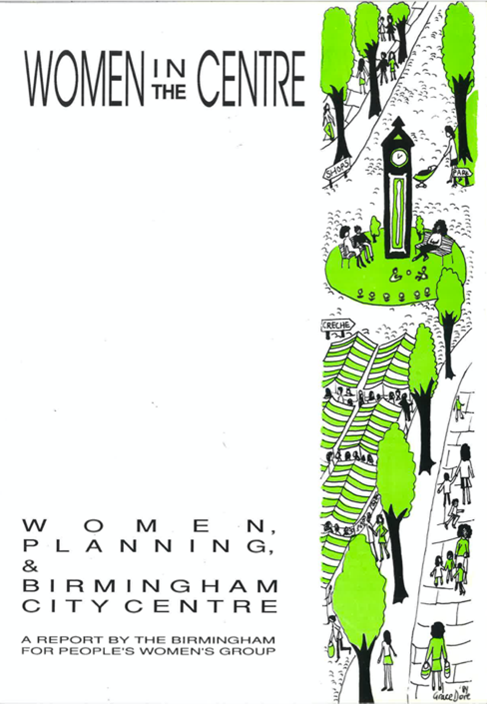

But the most sustained and influential campaign set up by women in Birmingham to specifically address the kinds of planning issues raised in Powell’s film was Birmingham for People’s Women’s Group. They emerged from the Birmingham for People (BfP) group that was made up of multiple community groups who had come together in 1988 to fight a controversial plan to redevelop the city centre Bullring shopping centre. But, as one of the BfP Women’s Group said:

“Right from the beginning I was quite critical of how the men’s voices just were heard and women’s voices weren’t. And so eventually a little group of women emerged who wanted to set up a separate group. I mean, we still attended the Birmingham for People meetings and activities, but we started wanting to carve out a role for ourselves because we just felt that as individual voices from the floor, and even the one or two women that were on the committee, you know, we were just being sidelined.”

Or as another BfP Women’s Group member put it, “listening to all these men gobbing on, and I said, ‘Where are the women in this?’ And we looked at each other – and that’s how it started.”

These women came out in force for the workshop and we were privileged to be part of what was in effect a reunion. The list of their impressive campaigns and collaborations is too long to elaborate all of them here, but central were the issues of access and safety. Access to the city centre via the subways, stairs and uncrossable roads was clearly an issue and the women conducted extensive surveys and produced detailed reports on the inadequate provision of public toilets, the dearth of baby changing rooms, places to breast feed and city centre creches.

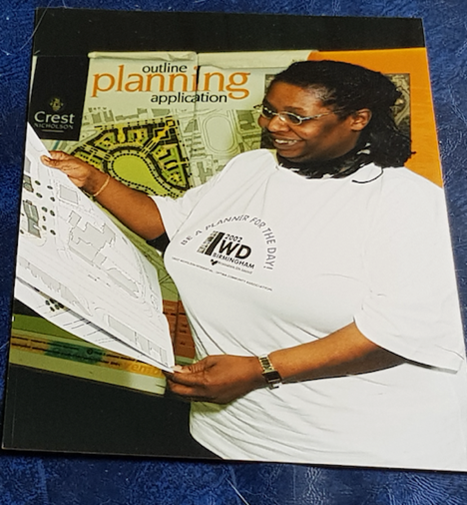

They set up street stalls to reach diverse women across the city and created a participatory safety audit tool to collaborate with residents in gathering evidence on women’s safety needs, recommending changes to the design of car parks, bus stops, housing estates, pedestrian routes and open spaces. They lobbied and collaborated through organising public meetings, conferences, residents’ planning days and meetings with communities, councillors, planning officers and developers. They made a video and ran training for women on the built environment, “So it was really, it was huge, wasn’t it?”. They worked with Bloomsbury Housing Estate in Nechells, East Birmingham, leading to the setting up the Safe Estate for Women’s group (SEW), a group that was particularly successful at reaching working class residents. They wanted change and to influence policy and over time their work became more, such as contributing to setting up and convening a cross-sectoral city-wide Women’s Safety task group collaborating with the voluntary sector, the local authority, the Police Community Safety Unit, the Planning Department and Passenger Transport Executive, amongst others. All of this work undoubtedly contributed to a shift in City Council policy from the late 1980s through the 1990s to a more people-friendly urban design approach, accommodating conservation and pedestrianisation and breaking up of the inner ring road (Cherry 1994).

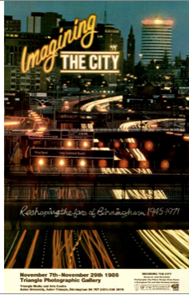

Underpinning many of the community planning campaigns in Birmingham were the problems inherent in the 1950s and 60s post-war top-down Modernist redevelopment, led by the city’s chief engineer, Herbert Manzoni, “at that time, there was a lot of urban regeneration, council estates were being redeveloped, tower blocks were coming down, new housing was being built. And nobody was talking to the people who live there about it” This was something that the exhibition, Imagining the City (1986), explored. Jude Bloomfield, a social historian, worked with photographer Roy Peters and designer Brain Homer to produce a critique of post-war planning. They interviewed and photographed “all the main protagonists of the redevelopment who were still alive at the time… The main thrust of the exhibition had been how the redevelopment had privileged the car and forced people underground in dirty and badly lit subways and made it very difficult to cross the city”. Women councillors from both ends of the political spectrum told Jude that they felt women’s concerns were excluded:

“She said, ‘you know, you used to go into a new building, very often the kitchen sink will be facing the wall’… And she’d say, ‘you know, it was just obviously designed by a man who’d never washed up’. And there were things of that kind which were very much to do with the imagination of the, planning the interior, where they had a critique of male lack of understanding.”

There was a certain frustration and sadness amongst the women in the workshop who felt the same issues were repeated over the decades, despite their efforts. One workshop participant’s mother had campaigned for adequate lighting in 1947, which was a crucial part of BfP Women’s Group’s safety campaigns in the 1990s. Whilst the issues of safety and toilets had come up “again and again, from the first redevelopment.” The women’s work on the Bloomsbury estate got forgotten as people moved on and out. Repetition and circularity thus occur with disrupted moments failing to materialise demands, which then emerged at a later date; or positive changes erased with a new rounds of redevelopments. The women’s toilets had improved in the 1990s but now there were few public toilets at all. Overall there was a tension between disruption and continuity, with questions raised about whether we were seeing a linearity and continuity – or something more sporadic and repetitive with similar issues emerging in different parts of the city in different forms at different times in response to changing political and economic contexts.

The use of visual representation to expose the issues came up again and again, with women’s community planning in Birmingham: in Paradise Circus and Imagining the City, but also a BfP Women’s Group ’s video Positive Planning and the wonderful, angry, witty photographs in ‘Birmingham: the business city’ exhibition, featuring photographer Rhonda Wilson, amongst others, and demonstrating the need for women planners in the city . Whilst more recently artist Cathy Wade’s video, For the Car, for the body (2017) based on research of Powell’s original film, explores a continuum from the past to the present in the city’s design still refuting women’s experiences.

Clearly feminist planning has in no way yet been ‘mainstreamed’, perhaps indicating the persistence of gender inequality, a view that the workshop women, whether their 20s, 50s or 70s, were in accord:

“I agree with you, I think while we’re living in a white supremacist patriarchy, this is going to be something that we’re going to be forever banging our head against. What we need to be doing is complete change, isn’t it, in terms of the systematic racism and sexism that oppresses us? in all areas of our lives? So, you know, I always felt that we did what we could. And, you know, we did as much as we could.”

Indeed, our workshop was also implicated regarding racial exclusion in planning as there was limited ethnic diversity amongst our group. This echoed the experience of BfP Women’s Group, which the members noted had similarly been dominated by white middle-class women. As one of the workshop members commented,

“What’s been mentioned is the lack of diversity in the group… I’m not sure what needs to be done, but I think it’s important because there’s a lot happening. There’s a lot happening in Handsworth, right now. There’s a lot happening in Aston. But what is it about these kinds of forums, why we don’t get the representation? … What’s also important is that these people are busy running their own groups anyway. Because I had circulated the flyer to a few people and there was someone I asked who’s active in the community… and she basically said, ‘Well, I’ll have to think about it, and what am I going to get out of it?’ So sometimes groups are tired of being researched? “.

This issue of racial exclusion is therefore a challenge that the Spaces of Hope team is making efforts to address and we welcome comments and input regarding this issue.

Nevertheless, BfP Women’s Group’s work highlights the importance of space and place for women in the city, with the grounded, socially-oriented and expansive holistic approach raising questions about the definitions and parameters of planning. What women want from a place is not confined to what might be termed ‘planning’, certainly not land-based planning. And a key desire emerging from the workshop was for their stories and struggles to be captured and remembered, combatting the circularity of forgetting.

References

Anawim https://anawim.co.uk/what-we-do/our-history/

Cherry, G.E. 1994. Birmingham: a study in geography, history and planning. John Wiley & Sons: Chichester. New York. Brisbane. Toronto. Singapore.

Powell, Heather. 1988. Paradise Circus. Birmingham Film and Video Workshop (BFVW) production.

‘Imagining The City’ photo exhibition. 1986. Birmingham Film and Video Workshop (BFVW) production. Photographer, Roy Peters; social historian, Jude Bloomfield; designer Brain Homer; curated by Roger Shannon and Jonnie Turpie.

Wade, Cathy Paradise Remix | Vivid Projects