How can images and aesthetics support community led campaigns? In this blog, Loraine Leeson draws on her experiences with the Docklands Community Poster Project, describing how certain images can become a powerful ‘currency’ for communicating issues and arguments to wider audiences.

The arts can be a highly effective tool in community-led planning due to their ability to communicate, consolidate and celebrate ideas. Where communication flows, this helps to unify thoughts, concepts and action, while celebration can serve to affirm a community’s identity as well as its collective power. The notion of aesthetics may seem more akin to high art, but in fact has a key role to play in community initiatives where the resonance of an image or event can help focus ideas and encourage engagement. This can be seen throughout history where powerful images of all kinds have served as icons summing up a spirit of collective endeavour, as in Delacroix’s figurative Liberty Leading the People or El Lissitzky’s abstract revolutionary poster Beat the Whites with the Red Wedge.

It is however not just image that is important, but also context. A painting in a gallery may be arresting but is limited in its ability to support community action. Artwork created for this purpose is most effective if it addresses both the particular context and intended audiences and is also embedded in the community’s strategy. Who is addressed through the proposals and to what end are both vital considerations for communication, therefore the nature of the relationship between artist/s and community is also of utmost importance.

© Peter Dunn and Loraine Leeson, Docklands Community Poster project

One factor influencing this relationship can be financial. Art production generally requires funding, involving both time and material costs. In recent decades however finance for art in social settings has increasingly come through commissioning by cultural or public institutions, or indeed via development agencies. Unless administered by an organisation supportive of the community’s endeavour, this top-down approach can effectively instrumentalise the artist within a pre-determined agenda, as cautioned by Stephen Pritchard. Even public funding can impose its own direction and, given that the stakes are high, all financing of arts intervention in regeneration is worthy of scrutiny.

As such it has become all too common for the arts and artists to be used to pave the way for gentrification. Always on the lookout for inexpensive studio space, artists readily occupy buildings emptied for development, their presence then encouraging changes in local retail and hospitality and leading to a shift in the demography. An example can be seen in the ever-eastward progress of the capital’s regeneration frontier. Once the inner reaches of East London had been colonised, the next stop was the impoverished borough of Barking and Dagenham. A myriad of cultural resources preceded the regeneration of this area including establishment of the White House arts centre and Serpentine North, a collaboration between Barking council and the Serpentine Gallery. This followed on the heels of initiatives such as the V&A Lansbury Micro Museum in Poplar, established by the V&A as a precursor to V&A East in the Olympic Park. Most recently LB Barking and Dagenham have commissioned a new development of minimally subsidised live/work spaces A House for Artists from which prospective inhabitants are required to run community arts activities. Further east the run-down seaside resort of Margate was given a major art institution the Turner Contemporary in the hope that it would attract visitors and revitalise the area. Sadly, as Jonathan Ward points out, this offered little either to existing residents or local artists and eventually the community got together with its artists and designers to co-create a Creative Land Trust to assist the region’s creative industries. In the meantime, arts-led regeneration has continued its creep along the south-east coast with the Folkstone Triennial and other high profile cultural initiatives.

© Peter Dunn and Loraine Leeson, Docklands Community Poster Project, 1985.

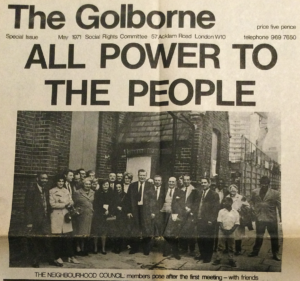

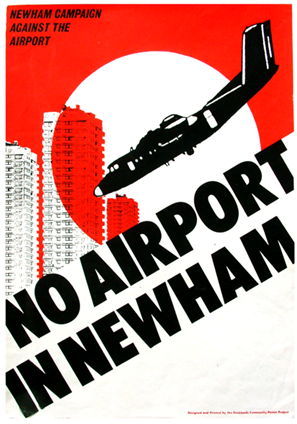

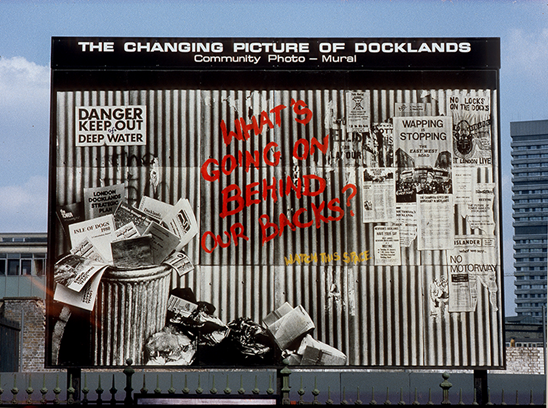

Set against these contemporary trends, groups such as the Docklands Community Poster Project that were part of the 1980s community campaigning over the London Docklands, were largely disregarded by the artworld, though also fortunate in preceding the later use of artists as regeneration’s cavalry scouts. The Docklands campaigners themselves, despite facing the juggernaut of Thatcherist redevelopment policies, also benefitted from being active at a time when the Greater London Council took a left turn and aided those trying to secure a future for the capital’s existing communities. For the arts group this long-term political support and subsidy enabled an effective relationship to develop between the artists, community and action groups, which themselves were involved in steering the organisation. As part of the project’s creative team I was able to experience the stimulus of working in a group representing a mixture of local, strategic and cultural knowledge. This combination of differing expertise led to the emergence of images and artworks that could not previously have been envisaged, as in the photo-mural sequences that traversed eight different billboard sites. Although the photo-murals themselves served a mainly local function, their reproduceable images also provided currency for disseminating the issues within a wider constituency.

What’s Going On?

© Peter Dunn and Loraine Leeson, Docklands Community Poster Project, 1982-5.

First image from the first sequence of photo-murals.

The photo-murals helped to consolidate and communicate the key ideas of the campaign, while photography provided resources for media purposes, and graphics and design contributed to initiatives that included the People’s Plan for the Royal Docks. The artwork produced reflected the progress of the campaigning strategies from oppositional to proactive and celebratory as the communities came to recognise their own strength. The People’s Armada to Parliament, organised by the Joint Docklands Action Group, was a show of force in which over a thousand people took to the river in an annual event over three years, while the Docklands dragon used on banners, letterheads and other ephemera, became the symbol of the fightback. Later in the decade the visual materials were combined into a travelling exhibition to accompany the Docklands Roadshow, a warning from the communities of the London Docklands that was taken to other urban centres facing similar redevelopment.

Photo © Peter Dunn and Loraine Leeson, Docklands Community Poster Project, 1984

Three terms of Conservative government prevented success in the overall Docklands campaign, however its lessons are still being used to inform community-led planning today. Its legacy for the arts is to demonstrate what can be achieved when artists, activists and communities work in symbiosis.

Dr Loraine Leeson is a visual artist who works through social engagement. Her practice and research focus on the role of art in social and environmental change through bringing community-based knowledge into the public domain. She is particularly known for her work with East London communities from the Docklands Community Poster Project of the 1980s to the recent Active Energy with older people, which received the RegenSW Arts and Green Energy award. Her monograph Art:Process:Change (Routledge, 2017) draws on forty years of her work to identify methodologies for creative approaches to social transformation. https://cspace.org.uk