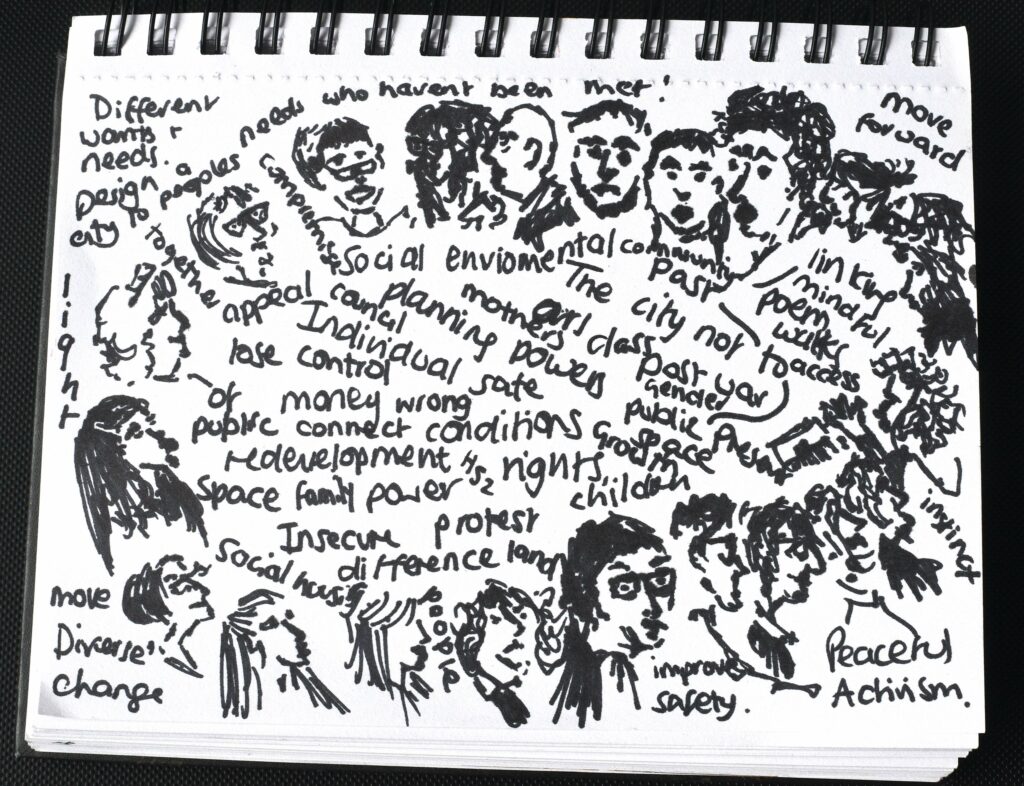

The Women in the Centre Walk, produced by Iris Bertz and Emily Baldwin in collaboration with the AHRC-funded Spaces of Hope research team, took place on August 5th 2023. It was part of a series of participatory events that engaged people from Birmingham in exploring the histories of women’s community-led planning in Birmingham from the 1970s to the 1990s. Through storytelling and mapmaking workshops, a collaboratively produced exhibition and film screening events at Grand Unions Arts Organisation, a dialogue was generated amongst past and contemporary campaigners about the past and present of women’s struggles to press for the places and spaces they need.

These dialogues informed the Women in the Centre walk in Birmingham City Centre, that you can access below. We hope you enjoy following in the footsteps of the women who came together to discuss their histories and contemporary campaigns, by following the route taken, with some historical and contemporary and information provided about each location. For further information you can look at the Birmingham Women’s Community Planning Case study page and a blog about our first Women in the Centre workshop in July 2022.

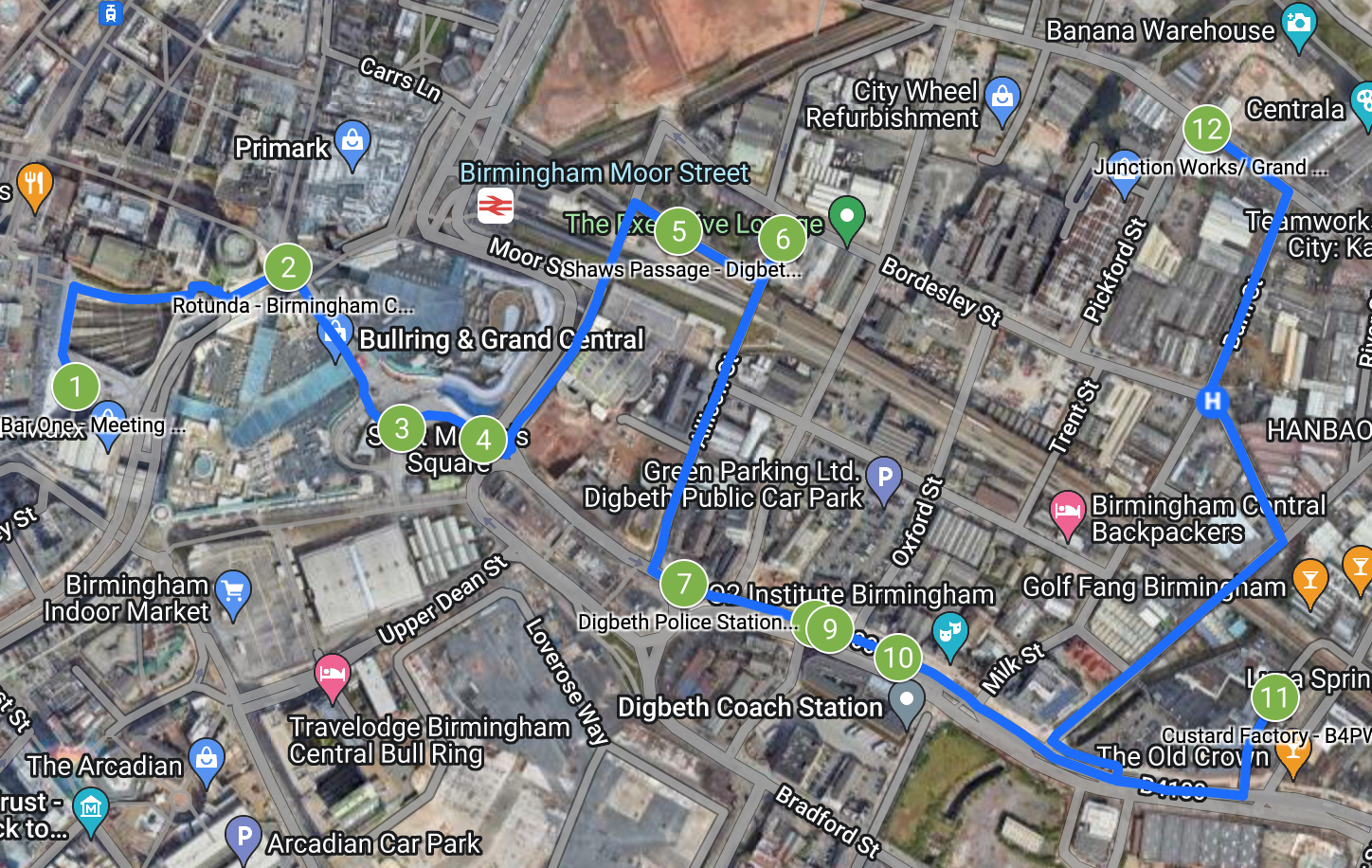

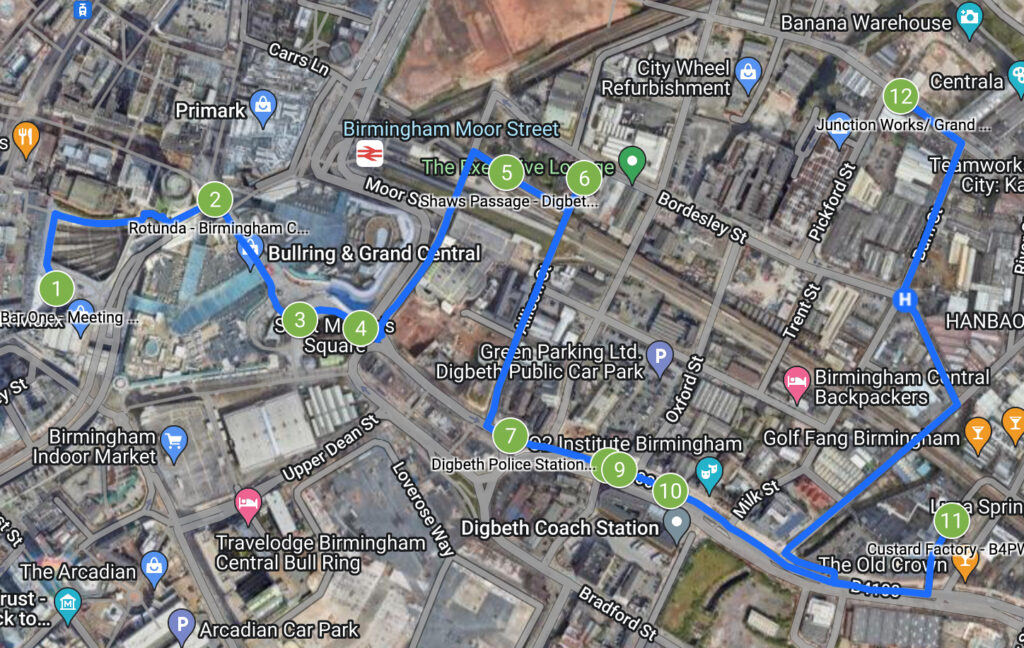

Google Map:

Google Map – This Google Map details the route of the walk and provides a short description at each point.

- The first blue layer details the walking route.

- The second green layer details the stops. You can find a description of each stop by clicking on the green number.

This Sheet also provides an overview of the route locations and their historical links.

Descriptions of Each Location

- All Bar One/Smallbrook Queensway:

The walk starts at All Bar One next to Smallbrook Queensway in order to contextualise the past and present issues facing women in public spaces in Birmingham. This is a busy spot for those coming in and out of the city by bus:it is crowded, lacks crossings and requires people to walk through a dimly-lit underpass or tight ramp to get to the city centre and Digbeth. It is hard to squeeze buggies, wheelchairs and families onto the path and the infrastructure is unwelcoming, especially for women walking towards the Bullring. Here we see that concerns of Brummy women decades before are still existing today. We heard from the women involved community planning in the 1980s and 1990s how they set up Birmingham for People’s Women’s Group (BfP Women’s Group) as a sub-group of the Birmingham for the People (BfP) group that brought local community groups together in 1988 to present alternative plans for the Bullring redevelopment. However, even in this grassroots community campaign, the women felt their voices and concerns were sidelined, so they set up their own sub-group to address women’s needs. BfP Women’s Group lasted until the mid 1990s and was highly influential. Their Mission Statement identified five key concerns: Choice, Access, Safety, Information and Redress. In practice this meant creating campaigns and alliances to improve pedestrian access across Birmingham’s inner city motorway ringroads, improve safety across the city in car parks, subways, bustops and housing estates, as well as fighting for more public toilets, baby changing rooms, breastfeeding facilities and city centre child care opportunities. They also worked to to improve information on women’s needs for planners, increase women’s participation in planning and provideeducational opportunities for women to pursue careers in planning and built environment professions.

- The Rotunda

We then proceeded to look up at the Rotunda, and to the left you can see the Birmingham City Council Building in the distance at the end of New Street. Both of these sites were important during the 1980s and 1990s. In contrast to the self-help emphasis of the women’s liberation movement that preceded them, BfP Women’s Group explicitly aimed to build relationships with the City Council in order to influence policymakers to include women’s perspectives in planning. They built relationships and alliances with The City Council, including with Les Sparks, Director of Planning, who was key to providing good links between the women and the planning department; with the City Council’s Women in Planning group and Community Saftety Group; with the Council’s community architect, to integrate women’s needs into the Housing Estate Action Programme for the Bloomsbury estate in Nechells; and BfP Women’s Group produced a video, Positive Planning, aimed at educating planners, that was partly funded by the planning department.

Chris Green, a City Council planner who was involved in the Birmingham City Council’s Women in Planning group, set up to promote women in planning and support women planners, speaks of how “women’s planning was in the air” and at this time and there were many crossovers between the grassroots and the authorities. For example, Heather Powell, who in 1988 directed Paradise Circus for channel 4 to highlight women’s planning needs and campaigns in Birmingham, went on to use her expertise when working for Birmingham City Council Equalities and Gender division in the early 1990s. She ran participatory planning events and describes the “sessions with ordinary working-class Birmingham women” in which they would take women around the city centre, “to look at the latest developments and ask for their opinions and how they thought things could be improved”. This included a visit to the top floor of the Rotunda to inform plans for the city centre redesign, “we had an amazing view across and beyond the city. The women pointed out a mistake in the design, which prevented people on foot from getting from one area of the city centre to another, which they took into consideration during the design.” This highlighted how crucial women’s experience and opinions were to the planning process, as well as how overlooked they were.

- St Martins Church

From here, we proceeded to the newset iteration of the historic Bullring market. Birmingham for People (BfP) fought for the retention of an outdoor market in the 1980s and 1990s, but it is also threatened today as it is starved out of existence due to poor accessibility for the community, leading to local action campaigns. For BfP and BfP Women’s Group, the city centre was their key site for political organisation. With many residents having been relocated outside of the city centre during the large-scale post-war demolition and redevelopment, participation in planning in this location was poor. In order to reach users of the city centre, where women constituted the majority of shoppers, BfP Women’s Group set up stalls and carried out surveys in the city centre marketplace. This enabled them to gather robust evidence on women’s experiences and needs in the city centre, shaping and strengthening campaigns on improving safety, public transport, lighting and urban design. This not only improved the situation for women with children, pushchairs and heavy shopping, but also for all city centre pedestrians.

- Digbeth Crossing

As the walk then continues to a series of crossings by St Martin’s Church, we begin walking towards Digbeth and the continuing problems with planning become apparent. Building works have eroded pavements, obstructed or prevented public transport, driven small businesses out of street side spots and overall made Digbeth extremely hard to navigate. The roads dominate the space, leaving pedestrians feeling confused and unsafe, echoing the experiences of women forced into dark and disorienting subways forty plus years earlier during the development of the inner city ringroads. Jude Bloomfield, a social historian, speaks of the extreme disorientation of the underground subways, which is expressed in Heather Powell’s film Paradise Circus (1988) as the result of a city redeveloped on the ideal of the commuting businessman,

“The city’s urban motorways that swept the visiting businessman into the central district and encircled it with a ‘concrete collar’ also cut the heart of the city off from its residential surrounds, pushing women with pushchairs and elderly pedestrians into dark, dangerous and disorienting subways: groups that bore the brunt of this discriminatory urban design’. We see that many of these issues still persist, as demolition and redevelopment continues apace in Birmingham, obliterating some of the earlier wins and creating new problems.

- Shaws Passage/ Digbeth Access Group

We then walked through Shaws Passage and it is noticable how this crossing can be confusing, with lots of different road surfaces and a lot of building work. In Digbeth there is a particular issue as major pedestrian routes from the city centre into Digbeth have been blocked and crucial walkways cut off by the HS2 construction, impacting access and businesses’ operation. Similarly to BfP Women’s Group’s strategy to collaborate widely with other voluntary and community organisations and the City Council, in response to the current planning problems, Digbeth organisations and businesses have come together to establish a Strategic Community and Business Group, the Digbeth Access Group, to work with the City Council to address the problems caused by redevelopment. A broad coalition in Digbeth has been developed, including the Grand Union Arts OrganisationBirmingham Friends of the Earth, ISE, Oval, Alison House Hostel, the Polish Centre and The Bond. They have met with the City Council and development representatives from HS2 and transport for West Midlands to work together to mitigate some of the issues caused by the HS2 construction work and poor environmental design in Digbeth. As such, the Digbeth Access Group has been able to address some of the accessibility issues by working with Interventaion Architecture to develop a new lighting and wayfinding proposal, using colour-coded walkways, thus improving orientation and safety. These routes and their design principles provide a model to be built upon in the future and they are currently applying for a project grant from Groundworks.

- The Warehouse/Friends of the Earth Building, 54-57 Allison St, Birmingham B5 5TH

The walk then takes you to The Warehouse in Digbeth, which remains home to many minority, activist and small community groups, including The Friends of the Earth’s community environmental building, Acorn Birmingham, Campaign Against the Arms Trade and Volunteering Matters. Jude Bloomfield, a social historian who researched post-war redevelopment in Bimringham, and Polly Feather, one of the BfP Women’s Group founders, stop here to discuss their experiences of earlier campaigns and community group actions.

- Digbeth Police Station, 113 Digbeth, Birmingham B5 6DT

At this stop, on the corner of Allison Street, you can see Digbeth Police station on the left, a Grade A listed building, built in 1911. However, when it was closed, there was a decline in the sense of safety locally. Safety was a key issue for BfP Women’s Group and they helped to establish and convene a cross-sectoral city-wide Community Safety Unit (CSU). Collaborating with the voluntary sector, the local authority, the Police Community Safety Unit, the Planning Department and Passenger Transport Executive, amongst others, the group steered significant safety improvements, creating a Safety Audit tool and making improvements to lighting and enviornmental design.

- Digbeth Coach Station, National Express House, Mill Ln, Birmingham B5 6DD

Just along from the police station is the Digbeth coach station. Despite an effective campaign by BfP Women’s Group to improve and increase public toilets in the city, many have now been closed and here is one of the few places where a public toilet can be found. However, you have to pay to use it! Yet again we see how the same struggles for a women- and people-freindly city recur again and again with access to public toilets remaining a key concern to women and families in the area. It is also challenging here to walk to by foot, especially with buggies or if using a wheelchair, plus being right next to the mainroad can leave you feeling very exposed, contirbutiing to a feeling of vulnerability amongst women.

- Smithfield Development Site

From here we can see the Smithfield site behind the coach station. Here we discussed the Smithfield redevelopment plan and issues for the queer community. Smithfield used to hold the wholesale markets and also the Indoor, Open and Rag markets in Birmingham. As the ‘city of a thousand trades’, these markets were extremely important to the city. Historic England considers Smithfield as a historically significant site because they regard it as the birthplace of Birmingham. There are even mediaeval remains beneath it. However,.a fire destroyed much of it in 2015, and it failed to recover. Then in 2018 the Birmingham wholesale market shut down, ready for demolition. And two multi storey carparks were demolished, leaving the Smithfield sitebare.

Since 2018, Birmingham Pride has been held on the site. This is the biggest LGBT+ festival in the UK and organisers argue that the site is the only place large enough to hold it in the city centre. Birmingham Pride boss, entrepreneur and community champion, Lawrence Barton, wrote to the developers of the site, arguing that the development is faliing in its commitment to create a world-class events space,

‘”The new Smithfield public realm is not fit for purpose as a world-class events space which was what we at Southside BID had been led to believe was being proposed. The public realm has shrunk significantly despite feedback given in earlier designs that it was already too small. The risks to this change in the plans are that popular festivals such as Birmingham Pride, Chinese New Year and Summer in Southside are now under threat as they have no space to host festivals of more than a few thousand people.”

The new proposed festival square site will only be able to hold around 7,000 people, ar short of the 40,000 who attend Pride. This not only reduces the city’s ability to hold large festivals that bring thousands of pounds to the city, but it also risks moving Birmingham Pride away from the historic and important Gay Village. This is also likely to be detrimental to all of the queer businesses that rely on pride to survive.

- Bus Stops

There are various bus stops along this route but many are currently out of service because of building works. Problems with public transport and the importance of community-sustaining infrastructure is touched upon by Immy Kaur, Co-Founder and Director of Civic Square, who argue for economic justice. She emphasises the pivotal role of land and social/civic infrastructure in neighbourhoods, and the value extracted from communities through our broken investment models. Civic Square’s work demonstrates neighbourhood-scale civic infrastructure for social and ecological transition, and they work with people and partners in the Ladywood arae of Birmingham. They work in practical ways to share alternative models of how homes and streets in Ladywood can be designed, owned and governed by the people who live there.

- Custard Factory, Gibb St, Deritend, Birmingham B9 4AA

BfP Women’s Group used to hold regular meetings at The Custard Factory, and more broadlyJude Bloomfield, researcher and social historian, shares with us how this building used to be a hub for diversity and opportunity. She interviewed people who worked and ran businesses from the Custard Factory in the 1980s and explains how the Custard Factory rented out studios and workspaces to micro and small businesses at low cost. This model was particularly favourable for the women’s pattern of employment, “who had portfolio-style careers, mixing home and work life, child care and employment in a public role, often in traditional handicrafts which sometimes started off as a domestic pursuit and then expanded”.

Relationships were cultivated in the city to access money and exposure for the place, with plans to grow medium-sized tech companies to cross subsidise the low rents for the artist and design companies. She describes how, “it was a socially managed space with a lovely communal garden-terrace, with an artificial lake-pool around which you could meet people casually.”. The interviews with the building’s tenants, revealed that they had a lot of social contact through sharing the space and were able to support each other and solve problems together. The space was subsidised and they were supprorted with information on marketing, promotion, government grants and export opportunities. However, when Jude returned 11 years later she was shocked to find the sociable design of the building had been eroded.’ “I recall being aghast at the changes. The outside lake place for socialising had gone. Access was much more difficult. Previously I could just go round and ask when it was convenient to interview people but the second time round it seemed to have been turned into a tech hosting centre… at the expense of the diversity of the businesses, squeezing out the women and small crafts.”

- Grand Union, Minerva Works, 158 Fazeley St, Birmingham B5 5RS

The Spaces of Hope/PeoplesPlans exhibition on women’s histories of community-led planning, two film screenings and a participatory discussion with more than 20 people and local campaigners was held at the Grand Union Arts Organisation. We wondered, where are the Spaces of Hope now? There is certainly no shortage of Birmingham campaigns, and although none are focused solely on women and planning, many are led by women and address inter-sectional iidentity needs, addressing issues for women, people of colour, LGBT+ groups and more. Current groups and campaigns still working at the grassroots for a people-freindly city include: Junction Works headed by Jo Capper and Cheryl Jones; Birmingham Open Media with Karen Newman; Rescuing the Historic Crown by New Street Station; Centrala, headed up by Alicja Kaczmarek; Civic Square, headed up by Immy Kaur and Yard/Maia, headed up by Amahra Spence.

Questions to Consider:

- Where are the spaces of hope today?

- How can local organisations collaborate with the city council today? Should they?

- What are some of the key concerns facing women, families, and marginailised groups trying to access Birmingham today? What is being done to help them?

- How do we recognise the impact of BFPWG on Birmingham today? What can be done to make this research known?

- Contributors:

- Debbie Humphry who led the Spaces of Hope fieldwork in Birmingham.

- Sue Brownill, Spaces of Hope project lead

- Polly Feather, Tonia Clark and Mary Ward of Birmingham for People Women’s Group

- Jude Bloomfield, social historian.

- Jo Capper and Cheryl Jones, Grand Union Arts Organisation and Digbeth Acess Group.

- Emily Baldwin, project support for Bertz Associates.

- Iris Bertz, Bertz Associates.

- Deborah Broomfield who connected Spaces of Hope with Bertz Associates; and is working with Spaces of Hope on the community planning histories led by black and brown racialised groups in Ladywood, Birmingham.

- Yingqi Lin, Photography for Bertz Associated

- Heather Powell, director of Paradise Circus (1988), produced by Birmingham Film & Video Workshop.

- Cathy Wade, Birmingham based artist, writer and academic, working with Vivid Projects, who hold Heather Powell’s film Paradise Circus (1988).

- And all the wonderful women who participated – you were vital to the success of the event, thank you so much for your contributions.