Whilst researching participatory planning in Birkenhead, the People’s Plans team have uncovered a documentary from the 1980s by Planning for Real pioneer, Tony Gibson.

Tony Gibson

A key figure in the history of participatory planning, Tony Gibson is best known for developing Planning for Real, a participatory approach that centres resident’s local knowledge of their neighbourhoods and empowers them to take action. Gibson experimented with early Planning for Real techniques in Birkenhead in the late 1970s, including the use of a vast 3D model of the neighbourhood, made up in sections by residents and local planners. Gibson, who worked with a group of local community members (the ‘Jubilee Project’), demonstrated how relations could be improved between local authority officers and planning professionals, and the people living in the area. He was subsequently invited by the Wirral Borough Council to follow up this initial work with a detailed survey within the Conway neighbourhood of the town.

New Communities Project

At the same time, the Town and Country Planning Association (TCPA) was investing in a programme called the New Communities Project, that would show “the different ways in which new communities can be created whether on edge-of-town sites or in existing built-up areas”, and to “encourage people to apply the new ideas and approaches […to…] existing urban area[s]”. The New Communities Project was led and largely designed by Gibson who was a TCPA project officer. As a stigmatised, urban area of high-rise social housing and high economic deprivation, Birkenhead was ideal for a project that aimed (according to Gibson) to see “how unused or underused resources could be put together to develop self-help enterprises to create employment, improve the environment, help the disadvantaged and restore some lost pride.” Crucially, it was an opportunity for Gibson to test his new methods.

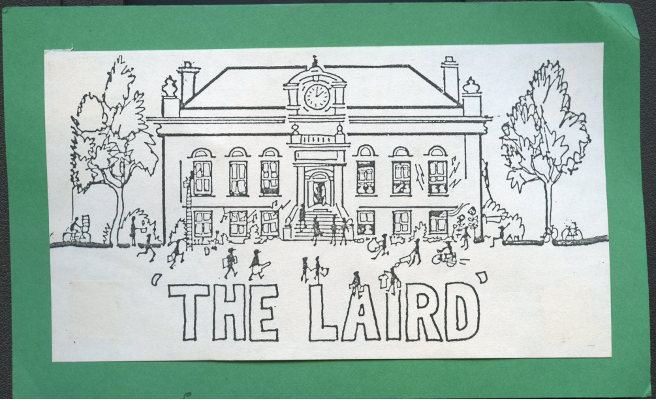

The Laird Enterprise Trust

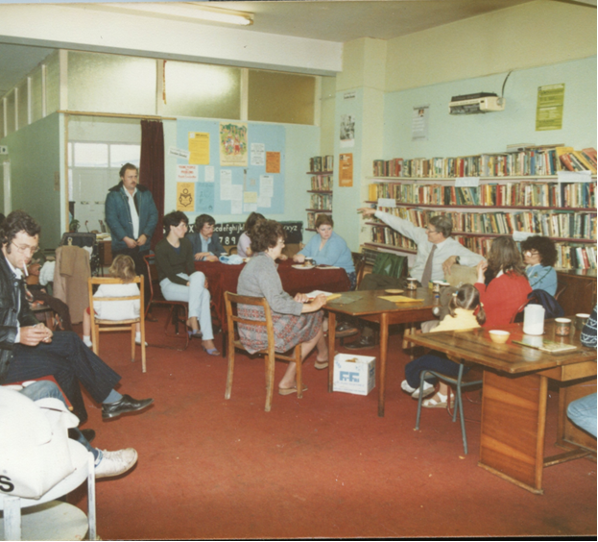

Gibson oversaw a period of community consultations including resident-led door-to-door surveys to capture how the community understood their local needs and resources. Today, we would understand this process as asset-based community development. A feasibility report titled Making the Most of Local Resources recommended that use should be made of a three-storey, Victorian building in the heart of the area, as a base for new activities. The disused building was once the home of the Birkenhead School of Art and an important local landmark. Its state of decay epitomized the plight of the whole neighbourhood, and its revitalization was seen as symbolic as well as functional. Multiple partners were brought together with the community and The Laird Enterprise Trust Association was instituted, with the ambition to turn the building into a local enterprise and skills hub. Though progress was delayed by a series of issues, by 1986 the building housed a variety of small creative enterprises including a potter, a dress designer, a signwriter and a furniture repair workshop. The project figured in a list of top Community Enterprise Awards and received a plaque and a money prize from the Prince of Wales on behalf of The Times and the RIBA. However, activities were soon halted by the discovery of dry rot in the building, which the Trust could not afford, nor raise funds to remedy. This led to the dispersal of activities and eventual disbanding of the Trust in 1990.

Good Neighbours

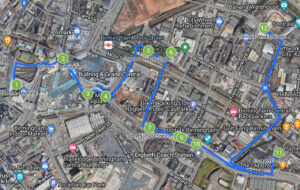

In 1988, Gibson made a documentary about the New Communities Project with Central Television titled Good Neighbours, which you can watch here. Much of the Good Neighbours documentary was filmed in Lightmoor near Telford. Lightmoor was a companion New Communities project to Birkenhead and in effect, Gibson was trying out the same experiments and techniques in two very different places. During our research in Birkenhead, I spoke with a former member of the Laird Enterprise Trust who described Lightmoor as a “hippie dippie middle class enclave”, with reference to the view that Lightmoor residents had greater personal and collective resources than those in Birkenhead. Where Gibson’s work in Birkenhead has largely been forgotten, Lightmoor is generally understood as a success, and is more discussed in the planning literature and in Gibson’s own writings. The Good Neighbours documentary includes interviews with Gibson who describes the challenges and opportunities of the two sites, which are often held in opposition due to the differing needs and resources of the communities and the specific geographies and histories of the local areas.

As the Good Neighbours documentary explains, the New Communities Project was an attempt to revive the utopianism of the Garden City for a new era of community action. It was as much about changing attitudes and encouraging people to realize their own potential as about changing the appearance of the neighbourhood. At People’s Plans, we’re particularly interested in Gibson’s range of strategies to emotionally influence people (both planning and policy professionals as well as residents), which raises interesting and relevant questions for planning and community action today. It is probably no co-incidence that the documentary’s title owes a heavy debt to the Australian daytime soap-opera, Neighbours (and its theme tune), whose extraordinary popularity peaked in the UK at that time with its imagined family-friendly, co-operative and enterprising community. As Richard Carr has argued, Neighbours charted the social transition away from Margaret Thatcher’s ‘no such thing as society’ tenure, towards the optimistic dawn of New Labour.

Given the contemporary significance of community action around urban and environmental issues, Gibson’s work shows that planning is not a purely technical or bureaucratic exercise but a complex multi-vocal process that engages deeply felt, affective attachments to place. This is particularly relevant in the context of New Towns which have recently returned to the policy agenda with the reinstatement of the New Towns All Party Parliamentary Group in 2022, as well as Labour Party promises to build new towns and new communities. If Gibson’s ultimate failure in Birkenhead highlights the challenges of funding and sustaining community projects, in retrospect the project anticipated many core ideas of community development and brings to light the responsibilities of practitioners and local leaders who work with community emotions and the feelings of place, to galvanise collective momentum.