Report by Debbie Humphry. Quotations are all from the participants involved in the Community Enterprises (CEs) unless otherwise indicated. Link to the Map Spaces of Hope – Map (peoplesplans.org)

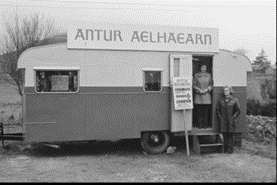

Back in July 2022, we visited one of our case study sites in Gwynedd, north west Wales, receiving a generous welcome from eleven of the many community enterprises (CEs) clustered in this region that had emerged since the 1970s. Whilst there are many examples of community enterprises across Wales and the rest of the UK, we were drawn to Gwynedd by their number and density in this one Welsh county and also because of their many firsts: Cymdeithas Tai Gwynedd, the first community housing association established in 1971; Antur Aelhaearn, the first community-owned cooperative of its kind in the UK, established as a pottery and knitting business in 1974; Nant Gwrtheyrn, the first Welsh language residential centre, converted from an uninhabited former quarry village in 1978; Antur Waunfawr, the first centre for people with learning disabilities to be trained and employed, established in 1984 and, Tafarn Y Fic, the oldest village cooperative pub in Europe bought by local people in 1988. We also knew this region had the highest percentage of Welsh speakers in all of Wales and was a stronghold for Welsh identity. So we wanted to find out more about what, why and how these asset-based community developments had emerged, sustained and multiplied over time in their various forms and, given the centrality of locality, place and space to these enterprises, in what ways could they be regarded as community-led planning?

The early ‘first wave’ of community enterprises came out of a period described as,

“A very exciting time in the history of Wales, generally, in the 60s and 70s when there was an upsurge in a national feeling here in Wales. The campaign for status for the Welsh language was gaining ground and a lot of us young generation were a part if you like of the general 60s movement for asserting ourselves and freedom… a time of creativity and of radical thinking and of trying to do things, of getting people involved in the future of their communities and their nation”.

However, radical action intersected with need, with the CEs also a response to de-industrialisation and disinvestment by public and private sectors in this former quarry region, which had led to reduced services, poor employment opportunities and persistent poverty. Even now, the growth of the tourist industry only offers insecure and low-paid employment, whilst the many second homes bought by the English have pressured steep house price rises. There is a sense of few options with an oft-repeated adage that local communities must do it for themselves because no one else will do it for them.

In this context, the CEs offer an alternative economic model: the chance for Welsh communities to collectively develop their own businesses and opportunities, grounded in their localities. Many of the CEs in Gwynedd were responding to abandoned businesses with pubs, hotels, shops, banks, libraries and leisure spaces taken over by local communities in the face of closure, adapted to local needs and functioning as community hubs.

“it’s the community itself deciding what we need. The pub has closed. The chapel has closed. The school is closed perhaps. And they say, well, we need a hub for this community. So they buy.”

Similarly, as services closed, communities took them on, from transport to food parcels to finding a space for the local choir to rehearse. These enterprises then typically expand as other sites become available, developing new spaces, functions and services. Each venture develops a mixed portfolio, spanning across a variety of social, community, cultural, industrial and commercial spaces and services. “We kind of own everything” said one CE member. The CEs represent an increasingly important economy, but also they represent a genuinely holistic form of regeneration, with community-led planning returning the social and cultural to land planning. Not everyone recognised what they were doing as planning but across the sites we visited, we found that the CEs had reshaped and regenerated buildings, developed land and public spaces, revitalised high streets, taken on closed-down schools and community centres, brought in green transport and energy systems and created new cultural, leisure and health hubs. The regeneration of place meant the regeneration of communities and the regeneration of hope.

The more we talked to people, the more we realised that the roots of the CE values reached back beyond the radical hope of the sixties to the histories of empire, industrialisation and English oppression. Bereft of state-hood, Welsh culture, language and identity survived through the concept of “a community of communities”, which was grounded in the long traditions of community-generated chapels, the co-operative movement, community medical aid, industrial union struggles and the mutual aid it generated, the interdependence required for sheep farming and the Welsh language movement, Cymdeithas yr Iaith, whose political philosophy, ‘cymdeithasiaeth’, was a form of community socialism. This helps explain the sheer quantity and persistence of the CE volunteers. One participant explains,

“So the way I’ve been brought up from my religion and my politics, you just have a deep held belief that you should serve your community. Tradition, that’s from Robert Owen onwards, we’ve been taught that, you know, communities, community Planning, it’s a part of your core beliefs… people organised and built their own chapels 200 years ago, it’s through Sunday schools that people learned to read and write. So there’s been a tradition of community-based planning going back a long time, as well as in the quarries, you know, wanting to start up a union to fight on your behalf. So this is the stories we receive from our families and I think it’s, it’s natural for us”

All the CEs we visited emphasised the importance of sustaining the Welsh culture and language, rooted in its repression by English Imperialism. One of the first CEs was the Welsh language residential centre, Nant Gwrtheyrn, and one of the most recent is the LLety Arall hotel aimed at travellers wanting to learn about Welsh culture and language. Many of the strong, networked leaders driving the Gwynedd CEs met through Welsh language activism and brought with them its ethos of non-violent, proactive solidarity, as well as the drive to protect Welsh identity. This is reflected in the enterprises’ use of Welsh language, sale of Welsh crafts, the heritage museums and the promotion of Welsh music in the community pubs, “It’s at the centre of what we do”.

As an economic alternative, the CE model has withstood the test of Covid. The fact CEs emerge from and serve their localities strengthens their commitment to weathering financial downturns; in contrast to multi-national ventures that come and go according to global spreadsheet market calculations, with no commitment to place. Wales is no stranger to the abrupt loss of economic stability, experienced time and again as waves of retreating industries have extracted and moved on. The CEs offer an alternative,

“It’s about keeping wealth as close to home as possible. So, what’s happened in this area over the years, is massive leakage of wealth. You know, trying to redress that in some way, I think it works … when it comes to Caernarfon, we haven’t, we’ve hardly lost a single retail unit since the pandemic because they’re all sort of small independents… (with) a stake in the area”.

The commitment to place ties into the notion of ‘restanza’, an Italian idea emerging from The Foundational Economy that values staying in place, “focused on the assets and strength of communities”. This is in marked contrast to the current UK government’s construction of places as lacking and left behind. Cwmni Bro Ffestiniog, a network of 15 CEs across the Ffestiniog valley came together in 2015 and explicitly embrace the notion of ‘restanza’. Research they conducted found that young people wanted to remain and build lives and livelihoods in their local areas (Cwmni Bro 2022), which was echoed across our fieldtrip sites.

Back in 1984 Raymond Williams commented that local place is the appropriate ground for building a movement,

“Ideally, a new movement comes out of new ideas being specified in particular places – then there may be a model being expressed which is adaptable to the interests of other places and scales of operation.” (Williams 2003, p.210).

Drawing on these ideas, the Cwmni Bro Ffestiniog network is keen to develop a wider network across Gwynedd, Wales and beyond, to build stronger solidarity and generate a political movement able to pressure the government into re-directing funds from the multinationals, with their extractive planning strategies, to the locally-invested CEs,

“The model of social enterprise and community development pioneered by Cwmni Bro Ffestiniog… can be emulated and adapted by communities across Wales, and beyond… Our communities need to empower, co-operate and politicise so as to change government priorities to favour supporting communities and the foundational economy rather than corporate capitalism”

The CEs offer a way of looking back in order to move forwards; of using the past to build something sustainable for the future. The ‘first wave’ enterprises are often invoked as inspiration and model for the ‘second wave’ that proliferated from the 1990s. Many of the original Anturs (as they are called in Wales, literal translation meaning ‘adventures’) are still surviving and significant, foreshadowing the Well-being of Future Generations Act 2015 that requires Welsh public bodies to consider the long-term impact of their decisions on future generations regarding poverty, health inequalities and climate change by improving working practices with communities,

“I think Antur Aelhaearn offers a blueprint… for the Future Generations Wellbeing Act. This was the original really, the Welsh government could have gone here, they were working towards improving people’s health and wellbeing in 1974 here. You know this future Generations Act, I’m a big supporter of it, but actually it’s a regurgitated idea from Antur Aelhaearn and the Anturs that followed in the past 40 or 50 years. So it’s a huge legacy… not just for us but for all of us.”

Many thanks indeed to all the participants who welcomed us so generously on our visit to Gwynedd in July 2022, giving us their precious time and trusting us with their stories.

Here is a list all the CEs we visited

Cymdeithas Tai Gwynedd (1971), the first rural community housing association that bought and restored 29 flats and houses in various villages, still rented cheaply to local people.

– Antur Aelhaearn (1974), the first CE cooperative of its kind in the UK, initially a pottery and knitting business, now provides several spaces and service. Run by elected Senedd.

– Nant Gwrtheyrn (1978), the first residential Welsh Language school converted from an uninhabited former quarry village that has attracted largescale investment. Cultural hub.

– Antur Waunfawr (1984). The first centre established for people with learning disabilities to be trained, employed and integrated into the wider community, still expanding.

– Tafarn y Fic, (1988), the oldest village cooperative community pub in Europe; sustains several social spaces, is connected to other village community ventures.

– Galeri (GL, 1992) buying & renting properties in Caernarfon to support development of an arts/cultural centre and maker/retail street for community benefit and city regeneration.

– Partneriaeth Ogwen (2003). Collaboration of 3 community councils,. Purchased unused properties on the high street, let as shops and affordable rent flats to raise money. Gifted other properties by local authority (eg school). Led to extensive development including Ogwen Community Energy (Ynni Ogwen, cooperative) & high street regeneration

– Siop Griffiths(2002/2016)- Yr Osaf: Community shop, cafe and other community and high street spaces, buildings and projects, enterprise, creative and digital workshops & skills. Started from 2002 work with confidence building with women in Penygroes.

– Cwmni Bro Ffestiniog (2015).Network of 15 enterprises in the Ffestiniog Valley including pub, hotels, bike park & hire, broadcast station, health centre, opera, learning disability and homelessness support, environmental project, playing fields, swimming pool, shop, café etc. (see ‘Radical Ffestiniog’ Blakely article and Restanza report). (Blenau FFestinog the town in Wales with the most social enterprises per capita)

– LLety Arall (2017). Community benefit society est. a Caernarfon hotel aimed at travellers wanting to develop their Welsh language and cultural understanding.

– Tafarn Y Plu (Feathers) LLanystumdwy (TP, 2019). Pub, incl. outdoor space for performers; field and bought a chapel converted for holiday let to raise revenue.

References

A Way Ahead? Empowering Restanza in a Slate Valley (2022), featuring research by Cwmni Bro

Foundational Economy Foundational Economy Collective

Williams, Raymond. 2003. Who Speaks for Wales? Nation, Culture, Identity. Edited by Daniel Williams. Cardiff: University of Wales Press.