What is ‘community-led planning’ and how has it been understood over the years? In this blog, Professor Glen O’Hara traces the history of the concept and its relationships with ‘civic society’, ‘regeneration’ and activism.

The concept of ‘community-led planning’ can have as many meanings as there are people to ask about it. Most recently, it has come to be associated with the ‘neighbourhood planning’ ideas of the UK’s Coalition Government of 2010-2015.

Under that Coalition’s Localism Act, small groups of residents could come together and inform the overall Development Plan with their own ideas and priorities: they could also play a role in deciding on planning permissions and Community Right to Build Orders.

Many local authorities have seized on these ideas to incorporate small groups into their own agendas. They have seemed particularly apposite and useful in rural areas and market towns, where they have adopted and adapted similar work to localist parish plans, themselves encouraged by government agencies.

This local, quite fragmented and partial effort, privileging residents who themselves are often the most vocal or organised, connects back to many histories of British planning and its discontents from the 1950s onwards.

Two themes are immediately evident: the first is the way in which ‘civil society’ often meant middle-class homeowners or younger, highly-educated residents; while the second point obvious in many available histories stresses just how difficult the British state increasingly found it to build anything, especially in the face of extremely articulate and well-organised protest movements. Motorways, particularly urban motorways such as the Westway in London, would be one case in point.

In reality, those traits are over-evident in the literature because they are uncomplicated to find, they are coded in ways that both academic and popular writers find it easy to understand, and because the available documentation from media sources, Public Inquiries and the like often preserves the words of the very visible and outspoken.

Areas ripe for development in the 1960s and 1970s were often also gentrifying quite quickly, as in North or (later) West London; young families with children could often be found at the forefront of movements opposing development imposed apparently ‘from above’. They inevitably attracted public and press attention.

Beyond this, there is in fact a hidden history of the connection between community-led planning and social changes in Britain. Far from the types of protestor who could go on to form the mainstay of established groupings such as the National Trust, English Heritage or Residents’ Associations (and in the 1980s could often be found in the Social Democratic Party or among Liberals), a much more radical reading of self-possession, self-actuation and self-starting could be found.

This emphasised, not street-by-street neighbourhood planning, still less the identity of a single parish, but the connections between people who had often been left out of post-war Britain’s determined, deterministic stories of social change: the marginalised poor; older people; women; racialised groups; and those seeking sexual or gender liberation.

These groups – in some ways to flourish in London during the 1980s – were not so much interested in appearance and design, but rather in the inner social and even moral workings of what planning could achieve or become.

This was obvious right across the United Kingdom (a trend perhaps unfortunately disguised by the emphasis on the new politics of large cities, particularly London). In Hull, student activists set up housing co-operatives. Advice units, a community newspaper and a network of charity workers sprung up in Cardiff.

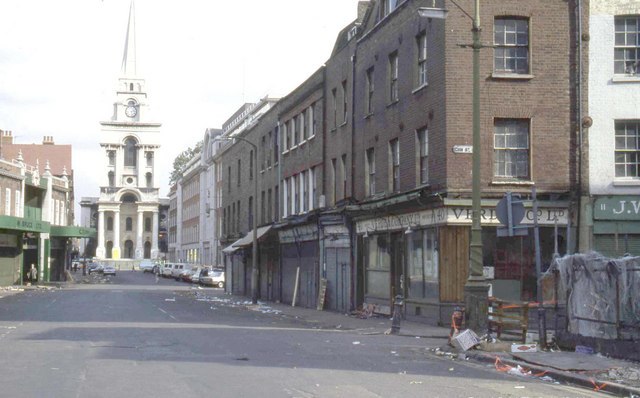

Around London’s Spitalfields (above), the Campaign for Homes in Central London and the Jagonari Asian Women’s Centre catalysed moves towards plans reflecting local needs: in Greater Manchester, Community Centres and a Water Adventure Centre for children provided hubs around which the people of Gorton and Hathershaw could reimagine the future of their areas.

In lots of these cases, a new type of academic was often to the fore, with the huge new intake of new universities of all sorts (as well as all sorts of Higher Education Colleges) providing a willing workforce of advocates and legal experts that would assist groups from outside the mainstream.

The expansion of Britain’s universities, planned from at least the time of the Robbins Report to increase productivity and efficiency, perhaps in this sense had the unintended consequence of undermining the state’s attempt to remake a streamlined, ‘rational’ and planned Britain, all designed to the same specifications.

Other experts, notably the Town and Country Planning Association, were also deeply involved in this new movement: its Mobile Planning Unit advised on controversial plans for the Divis Flats in Belfast during the mid-1980s: among other examples, the Association was also active in formulating ideas about the future of Conway in Birkenhead.

Just as new ideas were bubbling up from more general social changes, so the changing idea of ‘the expert’, to some extent connected to the university boom, was altering the idea of civil society as it related to planning itself. Increasingly, planning was not supposed to be for people or done to people, from ‘above’ – it was conducted alongside and with an increasingly fissiparous, hard-to-define and assertive public.

New civic activism – people of all sorts ‘doing things for themselves’ – ramped up especially as the economic and social context turned colder at a national level towards the end of the 1970s, and across the 1980s. As many voters turned away from collective solutions and a collaborative state, so groups that did want change took things into their own hands.

Overall, Britain’s history of community planning should assist us in reconceptualising what the idea of civil society really is. The Victorians and Edwardians thought this emanated from identity with, and pride in, a place – as the great urban public architecture of that era attests.

But between the 1960s and 1980s another meaning burgeoned: rather than the hyper-local emphasis on building and its problems that seems the prevalent discourse now, this was self-consciously novel, radical, connective, connected, seeking pride in links with fellow campaigners or residents. Reflecting wider social trends, groups moving increasingly from the periphery to the core of social life argued that they did not want help but self-help, not consultation but real voice, not a stake but a say. In that sense civil society was changing rapidly, a process for which the history of community-led planning allows us a ringside seat.

Glen O’Hara is Professor of Modern and Contemporary History at Oxford Brookes University. He is the author of a series of books and articles about modern Britain, the latest of which is The Politics of Water in Post-War Britain (2017). He is a regular commentator on politics and policy in the press, including for The Guardian and The New European, and is currently working on a book about the domestic politics of the Blair government between 1997 and 2007.