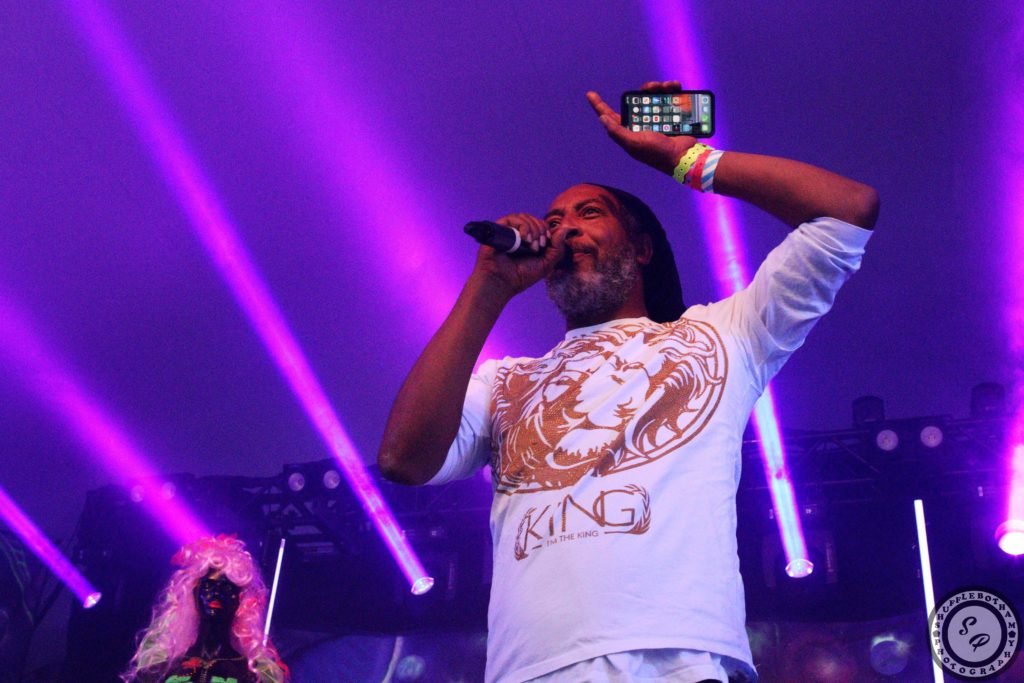

Debbie Humphry, talking to Coventry-based artist, documentary filmmaker and producer, Adrian Dowling.

Photographs by Jamie Shufflebotham

Adi Dowling arrived in Coventry from Dublin in the late 1970s, into a culture of de-industrialising despair, “as in poverty, racism, serious violence”. But from 1985 this all changed, when the violence of football hooliganism transmuted into the love of rave culture. He has since made numerous documentary films and podcasts showing the power and hope of young people as they claimed their own spaces and created new communities through music, ecstasy and dance. As a working-class man he is well-aware of who has the power to write history, whose voices get heard, which impelled him to tell the story of rave as he knew it.

“I always found history interesting. But I don’t think it’s honest enough. Whereas I document young people, what they were doing before ecstasy and the sound arrived, and how, you know, a movement or a youth revolution can change a whole generation. Because this worried me, the way the media and mainstream were documenting what had happened during that period. And it isn’t, it isn’t accurate. It is now because I’ve made 15 films so far and 24 radio documentaries. This is very, very honest.“

Raves are usually associated with London and Manchester, but Coventry is one of the key cities from which it emerged and the first place that a legal rave took place in 1990, as well as the first place to host a sanctioned 24-hour all-night dance club.

During the 1950s and 1960s, Coventry was known as the British Detroit due to its thriving car industry. Also, like Detroit, deindustrialisation in Coventry led to factory closures, unemployment and social and racial conflict. Yet in both cities a new influential urban dance movement emerged, Motown in Detroit (termed after the ‘motor’ city) and house and acid house ‘rave’ music in Coventry: what Adi calls “Coventry’s very own motown story”.

Small-scale dance parties led to the emergence of several organising groups setting up multiple dance events in and around Coventry. The ever-more ambitious and well-organised raves were held for dozens then hundreds then thousands of partygoers, in a car showroom, abandoned industrial estates, warehouses and fields. Within weeks of the first rave, young people’s sense of hope, self and other was transformed. Cultural groups that had been separated came to work together to put on raves and divides were bridged as formerly conflictual classes and ethnicities converged and communed. White football hooligans who had previously smashed up the Caribbean community’s sound systems now gave them respect for their exceptional skills as sound technicians, electricians, carpenters.

“It was magical, these lads making speakers themselves and the sound system culture got prestige. White men started to dance. In a space of a year and a half, something that had not happened over 50 years, the west Indian and Irish and English cultures came together through British street culture”.

Both groups had a history of conflict with the police but now they were creating music and shared spaces, against the system, together. New creative fused sound genres exploded – grime, jungle, hip hop, garage, drum and bass.

The challenge of organising the increasingly huge all-night parties in found public spaces, under-cover, with the fitting out of powerful music and lights systems, required the particular skills of precision-organising combined with flexible opportunism. This was about young people who had been facing the loss of hope and erosion of agency taking control of their own spaces, producing an alternative set of values and a wholly new kind of culture and community. They were finding their own power and capacity, making it up and creating it as they went along. Although Adi Dowling does not want to romanticise this time. For example, he documents the first ecstasy death and his next film will examine the negative impact of drugs. Nevertheless he is passionate about recording the achievements of working-class people and the broader historical changes they wrought.

“I can trace back a multi-billion pound industry to the four individuals in Coventry, which is crazy… Three or four young men that didn’t achieve an education, that are all from immigrant backgrounds, that were football hooligans. But when they found something that they wanted to be part of, that’s, so that’s it… it’s a social history. As in I’m not just explaining about this music thing. I’m explaining about how the world changed, and you know the football hooliganism, which was a mainstream British, this was an every week thing, and it stopped because young men and women started taking ecstasy and dancing.“

Raves present an alternative way of understanding public space, raising questions about its purpose and rights of access. Of course rave transmuted into a global capitalist industry, but its origins were in claiming unused spaces for their use value by and for the community, in direct confrontation with the exchange values underpinning the legal and planning systems. One empty warehouse was broken into and squatted for a rave, made good the next day, with no trace of the night before.

This led inevitably to a battle between the people and the state. The national government responded with new laws and heavy policing: the Entertainment (increased Penalties) Act 1990 enabled fines of up to £20,000 for hosting illegal raves or parties and the Criminal Justice and Public Order Act 1994 gave police the powers to stop and turn away vehicles within five miles of a rave. This heavy state response with restrictions on gatherings has disciplinary echoes with the current Police, Crime, Sentencing and Courts Act 2022. Thus, raves aimed to occupy space under the radar, in contrast to other community planning approaches that made public claims for space. This sometimes resulted in a comic twist to the principle of unintended consequences as ravers were guided to the secret locations by the light of police helicopters.

Eventually, Coventry was the first place where a legal all-night rave took place as the police, persistently outwitted and frustrated by the innovation of the rave organisers, invited them to a meeting to propose working together. When the dance organisers, Micky Lynas, Bambam Lynas and Neville Fivey of Amnesia House, set up as a Private Members’ Club, the police realised they had no way to shut them down and decided instead to work with them, “the police approached them and said look, we want to make you show us how to do it legally. So they changed the licensing law”. In an astonishing about-turn, the police found the rave organisers an in-use Sports Centre next door to a police training centre as a venue . The police brought the fire brigade in to advise on fire safety and how to convert the space by creating several new fire doors. Exactly the same model was later copied to convert a sports centre into The Sanctuary in Milton Keynes.

So it was that the formerly unlawful Amnesia House organisers put on the first sanctioned all-night legal rave in Coventry in 1990 (with six in total). One month later the Eclipse nightclub opened in Coventry city centre, copying Amnesia’s blueprint and getting the first ever 24-hour licence. The Eclipse was effectively the world’s first dance music super club, with performers and MCs coming from all over the UK and flown in from Europe and the States, such as Moby, 808 State, Frank the Wolf, Joey Beltram and Sasha. The Prodigy performed their first gig there for £40.

The significance of these changes to the licensing laws and the about-turn in the state’s approach to raves is hard to under-estimate. Coventry set the blueprint for a legal licenced rave and was copied the world over, opening the door to a multi-billion-pound global clubbing industry. These young written-off ravers were entrepreneurial, Adi says, “they were Thatcher’s children. They didn’t fit in, they failed academically but they wanted success. Selling tapes. Selling tickets. It went from 100 to 15,000 attendees. Young people black and white clicked together to make this thing and it goes global.”

Adi Dowling’s work aims to capture these historical shifts and in so doing he re-presents and re-values working-class culture and re-centres working class power. He brings in young people to work with him and at the Coventry City of Culture his exhibition drew in hundreds of working-class men and women. But Adi warns that we are returning yet again to a historical moment when young people are being marginalised, with youth services cut and a generation struggling to find secure affordable housing and decent jobs, “I don’t think England learnt that about, you know, you need to nurture young people… all these things create a kind of young person in history”. So Adi wants his work to inspire the next generation, to show that they too can be agents of change,

“How young men and young women that sort of get written off by society, they’re the ones that do the big things … So that’s what all my work is about really. I’m trying to sort of stimulate people like me, to the future… explaining the journey really, so that other people, you know, that possibly don’t think they’re capable of doing it can sort of make a mark on history.”

* * *

Find out more about Adi Dowling’s work here: https://www.reflectionmediaart.com