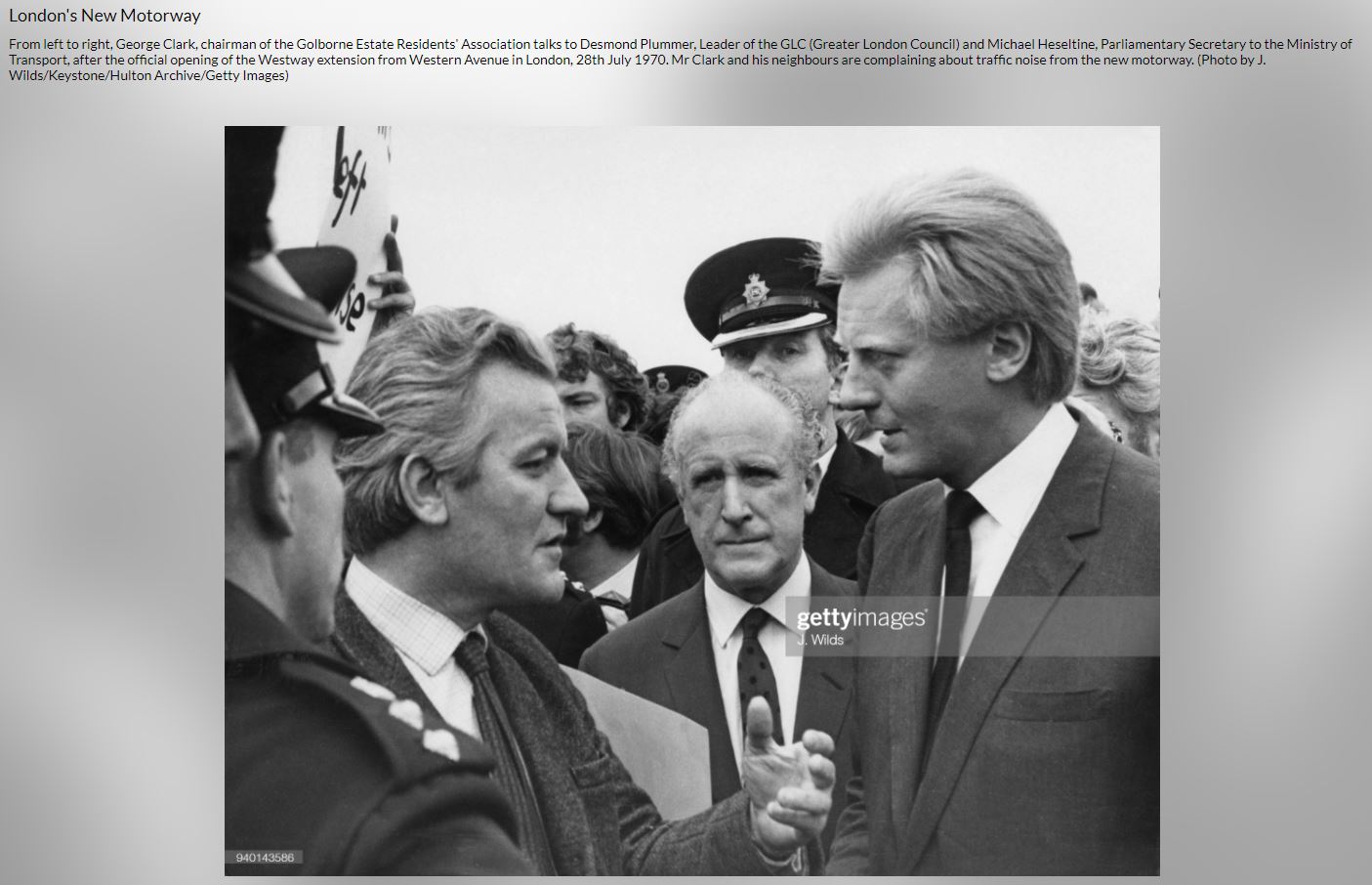

Long-time resident and activist, Adam Ritchie, reflects on one of the most significant episodes of community-led planning in London, focussed on the Westway road in North Kensington.

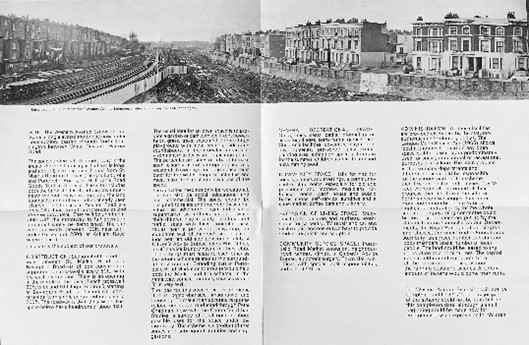

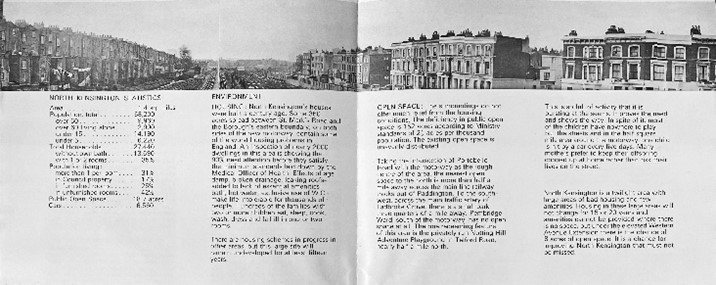

The Times Newspaper concluded that every mile of Westway cost the moving or eviction of 5000 families. North Kensington, over which it passed, had 64% of its houses overcrowded and substantially “under maintained”, to put it mildly. Some said it had the worst slum housing in Britain.

I had lived in the area for a long time before moving to work in New York from 1962-66. When I returned, I went to see a playground on Acklam Road on the now derelict land where Westway was to be built. It had been started by the London Free School and John Hopkins, an old friend of mine.

An interesting site it was, at basement level between Acklam Road and the Metropolitan Line railway, about 30-45 m wide and 220 m long. The rubble from the demolished houses was largely still there so the local kids climbed over the protective brick wall and managed to slide or clamber down a narrow beam onto the site below. There they made imaginative use of all the joists and bricks and building rubble to construct their own buildings.

I liked their structures so much that I bought a couple of hammers, a kilo of big nails and a saw, which I hid under the rubble when there was no one there. The structures had disappeared, and four larger and much more adventurous structures had been built from the detritus of the old demolished buildings. Now they had windows and doors and from the platform they had made, the kids projected a long board tied at the far end to an old tyre. The kids would run from their platform along the board then jump on the tyre and dive on to several mattresses to cushion their leaps. My hammer, nails and saw had had a galvanising effect. The site was not at all easily accessible to adults physically, but mums frequently looked over the wall at Auckland Road and yelled at their kids, “Tea’s ready”, or “Don’t bloody get dirt on those shorts”.

The kids felt themselves independently safe on their site but they knew they were within sight and earshot of adults if needed.

Considering the enormous mass and political momentum of the building of the longest stretch of elevated motorway in Europe about to be built here, I thought that claims must be made as soon, as urgently as possible by and for the local community.

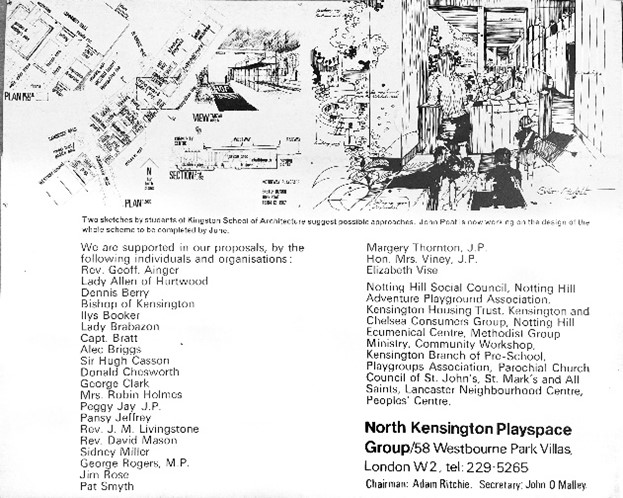

At the final meeting of the London Free School, I said that I would fight for the inclusion of an adventure playground on the Westway site and asked others to join me. Eight joined that night, including John O’Malley, a local community worker. We all met weekly for the next 4 years. I became chair and John secretary. We called ourselves the North Kensington Playspace Group.

We got the plans for the elevated motorway and immediately saw that 8-acres of the 23-acre construction were marked as car parks. They would be housed at ground level behind 16ft high concrete planks with appropriate entrances for each section. Only one in ten inhabitants had a car and the streets were never fully parked, so the car park must be designed for commuters which would bring far more cars on to North Kensington streets. With a 152-acre deficit in public open space, children played in the streets. The eight-acre influx of commuter cars would increase the car/child injury and death rate.

We decided to enlarge our brief. We would fight to get the whole 23 acres for local community facilities. We changed our name to the Motorway Development Trust.

We had many meetings with local organisations and public meetings where we pinned a 15ft plan of the motorway and provided pens and sticky notes so that people could write what was needed and stick on the vast plan exactly where it would be needed most. Nurseries, playgroups, a public laundry, a library, pocket parks, adventure playground, workshops, artist studios, training centres, a theatre, exhibition wall, Citizens Advice Centre, neighbourhood centre, a supermarket, workshops providing jobs, health centre, doctors surgery. After several such meetings, the suggestions, which were all very practical and answered the local needs, became the basis of our proposals.

We went to Kingston University and asked the students in the architecture department to draw up schemes to illustrate these proposals. John Poat drew an excellent design for a small section near Ladbroke Grove and later designed an ingeniously pocket folded A3 incorporating his drawing with useful text and a photograph of Acklam Road and the demolished houses.

Motorways we’re having a bad press at the time, so the British Road Federation gave us their bay at the British Motor Show and paid for the cost of our exhibition.

We fed stories to the local newspapers nearly every week and created a small following there. We needed to get to the Greater London Council and although having no hope of getting any interest or help from the Royal Borough, we started telling some of the Tory councilors about these plans for the community use of the space under Westway. We got in touch with architectural journalists. We lobbied the up-market trustees of local organisations to get their support. The Tory GLC and the Tory local council were all more persuaded by knighted dignitaries than other people. I took tea with Gay Christiansen, the Hon Sec. of the Kensington Society, at her house at 18 Kensington Square. I had tea with the sister of Sir Malby Crofton, leader of RBKC. These were intended to spread the word and reassure them that we weren’t radical tearaways intent on destroying everything they held dear. They would tell others of the meetings and we hoped our plans would not raise barriers and alarms. We wrote hundreds of letters outlining the plans to potential supporters.

We arranged to meet the heads of the GLC Transport, Parks and Planning Committees. Two days before the meeting, the Town Clerk phoned to ask if was just me and John O’Malley who would be coming. I said we would be coming, supported by Peggy Jay, recent former Head of the GLC Parks Committee, Sir Hugh Casson, President of the Royal Academy and planning consultant to six major cities across the world, the Clerk to the largest London charity and Ilys Booker, an internationally respected sociologist currently working in North Kensington. There was an audible intake of breath on the phone.

When we all got there, it was no longer as small meeting where we could be told to bugger off. There were forty or more already in the room. That morning we had half a page in the Guardian describing our scheme in detailed and glowing terms and a leader in the Times saying it would be shameful if this opportunity to build our scheme was lost. We had been desperately trying to get John Poat’s leaflet printed in time for the meeting and in the end, five minutes after the meeting started, John came in, in his motorcycle gear, still wet with rain, and distributed the very professional looking leaflets to everyone in the room. Very dramatic.

John Vigars (Transport Committee) said they would consider our plans but of course, the concrete planks for the car park were already made and would be put up anyway. He also described the impossibility of changing existing plans, which, of course, already had planning permission. Hugh Casson made a decisive speech describing the plank wall as ‘the Berlin Wall for North Kensington. Peggy Jay described how things could be done within existing GLC and Royal Borough operations. Our charity clerk said though most of the community facilities proposed were the responsibility of local authorities, his charity would do their best to fill the cracks. They agreed to further meetings to look into possible implementation of the scheme. John Vigars said that they would consider passing the administration of Westway at street level to RBKC.

A few days later, I described the meeting to Donald Chesworth of the Notting Hill Social Council. He said he had been on the GLC Planning Committee when it was decided and he had no recollection of the car park getting planning permission. As we had gone to a barrister to see if there was any way we could overturn the car park permission and we’re told no, there was no way, it was with some pleasure that I phoned the GLC Town Clerk and asked if he could send me a copy of the minutes of the meeting when planning permission for the car park had been given. He said he would see if they were still available. The same day, several large trailer trucks piled high the 16ft concrete planks were quietly driven away from the Westway construction site and we heard no more of them.

We went to the City Parochial Foundation and told them we hoped RBKC would set up the Westway scheme we were proposing, but we thought they had historically been very unwilling to support people in North Kensington and hoped that the CPF would make funds available to help get the scheme started, if RBKC actually did set up a charitable body to run the scheme. The Clerk agreed to earmark £20,000 (£400,000 in today’s money!).This was an astonishingly generous, imaginative offer. Not money for us, but future money to be set aside for an organisation that might never happen. Without it, I think the whole thing would ended up in the Council’s files with nothing happening in North Kensington at all.

It was a desperate situation for us. We had won the argument, but we would probably lose the whole war. We had decided to campaign from the beginning because if we didn’t, we would get the noise and pollution from 47,000 cars racing or crawling on Westway above and eight acres of commuter cars below. All completely negative effects to add to the already existing deprivations for the community, If we campaigned and got some facilities built, they would be at least some improvement, we hoped.

Finally, Sir Malby Crofton announced a scheme to set up a charity to run a scheme under Westway. The Town Clerk was to be Secretary, The Borough Treasurer, the Treasurer, Sir Malby Crofton would choose the Chair and invite certain organisations to sit on the Management Committee. John O’Malley and I were not to be invited to the new organisation. We sent a copy of his constitution to the Charity Commissioners, who rejected it as a body apparently set up with the sole purpose of subsidising Council expenditure. After a while, with a slightly different constitution, the North Kensington Amenity Trust was set up. Sir Patrick Reilly, a diplomat, was the first Chair. John and I asked two long established organisations to nominate us to the committee as the Motorway Development Trust was not one of the nominating bodies. The meetings were long and turgid. Everything we proposed was turned down or shunted into the bushes. Or there was no money, or no one available to do anything or the project might be run by unacceptable people. The whole thing was tightly run by the Council. Later, when a Councilor and John were jointly responsibility for calling meetings, the Councilor refused to call meetings or agree any meetings requested by John, so there were no meetings for ages.

The first Director, Anthony Perry, almost never got the Council to agree to anything they hadn’t proposed. The second Director, Roger Maitland, appeared to see the local community as the enemy and sued someone for libel for their account of what Roger was doing to them. The legal counsel for his libel case was paid by the Trust. Some bays were let for garages, a timber yard, Portobello Hall was built and run very successfully as a music venue for some years. Portobello Green was opened, a partly tent covered market was opened. Architects had a office and various shops opened in the Portobello Arcade. At the far western end, some sports facilities appeared. A public laundry and children’s centre was fought for and opened by local initiative. A skate park was set up at the eastern end.

It just never felt like the space was run to create facilities for the area. The Trust was run to make as much rent as possible and keep any of the messy, argumentative locals away. Troublemakers were evicted. There was no sense of a partnership run for the benefit of the local community. It was very disappointing.

I was elected as President of the Amenity Trust, a pointless gesture, the president having no powers at all, but it was the only power the local members of the Trust had. Soon after I left the Trust. In every way it had and has felt like fifty years of wasted opportunity.

We ran play schemes in the summers while the new Westway motorway was being built under the motorway and in temporary sites we found. The photographs were all taken on these sites in 1967-69.

In the years prior to the Grenfell Tower tragedy the local community had started to organise and oppose the gentrification of North Kensington. Groups like Westway23, the Grenfell Action Group and the Save Silchester Campaign began to hold the Council and other stakeholders to account.

The Save Wornington Campaign worked to successfully stop the destruction of Wornington College by RBKC for redevelopment as a luxury flats and ensure the continuing provision of adult learning in the North of the Borough. The Dept. of Education bought the building, invested £10 million refurbishment and leased it to Morley College.

The Friends of North Kensington Library prevented the much-loved library in Ladbroke Grove from being bought by the Deputy Head of the Planning Committee, closed down and leased to a private Prep School. It remains as a Public Library.

The Grenfell Inquiry was set up. At Westway, the Tutu Foundation started an inquiry into racism at the Trust. In the end the Trust was found guilty of ‘Institutional Racism’. There had to be big changes at the Trust. The Trustees, including the Chair, resigned and the senior staff resigned.

For the first time in fifty years, there is at last some sort of local control. There is a new Chief Executive Officer. The Chair of Trustees is local and has been involved in the local community groups fighting for change. Now we have the opportunity of turning the Westway Trust into an organisation for making the 23 acres under Westway for the benefit of the local community. It has taken over fifty years, but one must remain hopeful.